|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

SILVER EDITION

|

|

SILVER EDITION |

|

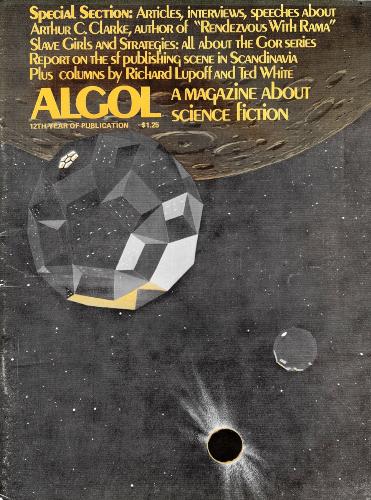

Slave Girls And Strategies by William Lanahan Copyright 1974 by William Lanahan Published in 1974 by Andrew Porter, New York NY, USA Printed in Algol - A Magazine About Science Fiction Vol 12 No. 1, Issue No. 23, November 1974, pages 22 through 26 US 1.25, 56 pages Front Back Copy Scanned by Jon Ard (Morgus) (20100701 01:11:00) |

Notes

NotesIllustration by Terry Austin.

Text

TextThe most popular writer now working in the tradition of heroic fantasy is probably John Norman. His chronicles of Gor, the counterearth, have thus far filled seven volumes. The conventional analysis of these novels will, however, fail to find immediate literary merit: the plotting is thin, characterization is sketchy, the reservoir of fictional invention supplies few surprises. The facile explanation of the polularity of the series is to remark the abundance of complacent and accessible slavegirls in the dramatic cast.

Yet there are more serious and respectable grounds for reading the Gor chronicles. The reader must first recognize that Tarl Cabot, the hero-narrator, is largely a fool. The reader should detect that, behind the many disguises and aliases he assumes, Cabot imitates a wide range of literary heroes, including Ivanhoe, Spartacus, Marco Polo, and Captain Blood, without ever achieving the archetypal level. Cbot never really knows what he is doing. This irony permeates the series and creates its value.

When he first introduces himself to the reader, Cabot speculates about the significance of his own name. Although he flatly denies any family kinship with the Italian Cabot who explored the New World for England, he pledges emotional allegiance to that alain who adventured forth into the unknown on behalf of a sovereign power other than his own. In effect, Cabot begins as an unloved orphan; without scholarly credentials he accepts; almost in disguise, a teaching post in New England. The disguise of identity, the uncetainty about his own talents, the acceptance of a role assigned by others rather than chosen by himself, the transfer from the familiar world of England to the setting in New England which acts like a distorted reflection to the place left behind: these are characteristics which will adhere to Cabot throughout the Gor chronicles.

Cabot comes to America to excape stagnation in his aunt's home; he goes camping to escape the pressures of teaching. He is carried off to Gor, the counterearth on the opposite side of the sun, to be trained as a warrior and to destroy the city threatening his father's domain. For Cabot, motive is always more urgent than purpose. He acts, and reacts, out of emotion and inuition; he is subject to anger, impatience, vengefulness, lust, self-contempt, pity. His missions are never of his own choice.

For Cabot, rational purpose is extrinsic and mysterious. His own conflict take place between his will to accomplish a mission and his emotions. Pity frequently moves him to refuse to exploit those who could serve the successful achievement of his quest. He yields to the love of a woman only when circomstances reduce the urgency of his mission or the lack of opportunity removes the possibility of success. When the woman, at that moment always his slavegirl, is more available than his quest, he enjoys her without guilt or preoccupation.

Instinctively he knows what men will do, but he rarely understands what women will do. Since men on Gor learn to act like men while women learn to feel like women, Cabot intuits reflex actions better than emotional attitudes. Wherever he goes, Cabot is either loved or hated immediately, and this depends on how those he confronts react to his humane attitudes towards people: the cruel hate him, the gentle love him. In fact, he sometimes turns hatred to love by inducing his antagonists to expericence their own humanity. Yet Cabot never understands why anyone loves him.

Cabot is the main character and chief narrator of the first six volumes of the series; in only one volume, the sixth, does Cabot finds himself without some task imposed on him by a superior. The sixth novel dramatizes his total moral degeneration into lust and cruelty as he assumes the personality of a pirate. He apprears briefly at the end of the seventh volume as the comfortably domesticated victom whose murder is planned by those who bring Elinor Brinton from Earth to Gor as their weapon against him. Elinor is the heroine and narrator of this volume and her experience is much like Cabot's: her passions and instincts drive her toward the fulfilment of desires which are, in fact, merely isolated elements to be manipulated in the larger programs of those who utilize her. Those who use Elionor for their own puposes are the enemies of the Priest-Kings of Gor, Cabot's employers during most of his adventures. The role that Elinor plays has been played in earlier volumes by Elizabeth Cardwell: transported to Gor by those who seek to destroy Cabot, she finds herself reduced to slavery, subjugated by her own erotic desires, and finally instrumental in wiping out the agents who have kidnapped her.

Cabot functions therefore as the center of a system of opposed and counterbalanced values: instinctive motive versus rational purpose; self-assured warrior versus terrified slavegirl; Priest-Kings versus The Others. The Others arrive in the series only at the fourth volume. The conflict of the first volume combines a political struggle between Cabot's father and the charismatic dictator Marlenus with a love-hate struggle between Cabot and the dictator's daughter. The second volume relates the struggle between the enslaved men and the aggressive women of Tharna, where the women wear silver masks, the men wear grey tunics, there are no poets and no taverns, and there are dungeons and mines for the unwary visitor. The queen of Tharna enslaves Cabot and he subsequently enslaves her. By the third volume, Cabot reaches the mountain citadel of the Priest-Kings, intent on revenging their destruction of his home and family, only to find a struggle proceeding between the factions of the ruthless Sarm and the sympathetic Misk. In the four later novel The Others, anarchical and cannibalistic but technologically proficient monsters, work behind Cabot's human enemies to destroy the power of the {riest-Kings by killing him. Only once does an Other appear clearly enough to be described, and then he ie seen, ironically, not by Cabot but by Elinor Brinton. Just as the Priest-Kings are gigantic bees, symbolic of man's social consiousness, The Other is a huge bear, man's mythic duplicate in violence and aggressiveness. Man is midpoint between the polarities of his own nature.

If man is to be identified as a species on Gor, this can be done by contrasting him with the other species capable of speech. The Spider-People are rational and gentle; the Priest-Kings are rational and pitiless; the Others are irrational and pitiless. Man is subrational and capable of compassion. Man, as personified by Cabot, is as capable of cuelty as of pity, but the pity is normal and the cruelty is aunique and irritable reaction to treachery. Cabot can be brutal to Talena, the dictator's daughter who is later to become his wife, when she pledges a truce with him only to attempt twice to stab him and allow his capture by his enemies; he can be brutal to Talima, the swamp girl who is later to become his concubine, when she reminds him that he has betrayed his honor by preferring life as a slave to death as a warroir. When Cabot disguises Vika, the slavegirl who has enticed him towards destruction in the citadel of the Priest-Kings, he wishes ostensibly to save her life by passing her off as a specimen in the zoo; the disguise requires that she be stripped, her head shaved, and that she be locked into a cage, the punishments inflicted on the medieval whore. Normally Cabot is so compasssionate that he inspires friendship and love by reason of the pity he shows, although pity is considered a weakness on Gor. His behavior is not atypical for the Gorean warrior: every warrior in the series begins an afaair by abusing a slavegirl and concludes it by marrying her, passing from bully to husband via pity and love. Thos process becomes so inevitable by the seventh volume tha Elinor's warrior lover sells her into slavery before he loses his freedom in marriage; he must then suffer physical torture and personal humiliation in order to reclaim her.

Gor is obviously a harsh planet. Its beauty consists in its sky, its water, its colorfulness, its spaciousness. Every living thing on it is a voracious predator, from the leech plants to the tarns or gigantic riding-hawks. Even the mice and the songbirds are equipped with horns; its nocturnal fauna are vicious and loathsome. The kaiila or camel does not suckle its young; the mother drops her offspring near some herd of wild game and the newborn kaiila begins hunting its food from birth. The tarn will tear its rider to shreds on the least excuse.

Yet even the tarn can be tamed, can be trained to some kind of affection. Soon after arriving on Gor, Cabot acquires a huge bird which he gradually turns into a pet. The peculiar ability of this hawk to turn up fortuitously at Cabot's moments of direst distress throughout the volumes emphasizes simultaneously a strength of theme and a weakness of plotting in the Gor chronicles. Pity acts for Cabot as the necessary prerequisite to love, and love is the only solution available for the core problem on Gor, the irreducible opposition of its component parts. Cabot pities and loves and rescues often in the course of the novels; in turn, he receives the same saving treatment from his friends, his women, his tarn. In every novel Cabot must be resued from his enemies at the moment of death by some deus ex machina. As grtuitous coincidence it is poor plotting; as motivated behavior it is the whole point.

Cabot's successes always result from a dual. His weapon may be sword, tarn or pirate ship. If a single companion aids him, he becomes dependant on that companion, whether slavegirl or untested adolescent. Less violent duels are fought successfully by such secondary characters as bettors and chass-asters'whenever Cabot bets or plays, inevitably he loses.

Cabot is loved by women, befriended by men and Priest-Kings, worshipped by his tarn, but he never understands why> He never fully recognizes his own naive vulnerability, his own simplistic attitudes, explaining himself on rare occasions as foolish or gullible. He never fully recognizes the brutalizing culture of the planet on which he finds himself; he excuses the culture complacently as a biological process which destroys the weak in order to strengthen the species. But Cabot will not kill arbitrarily. For him, biology is purposive; for him, purpose is mysterious, impenetrable, self-sufficient. What is purposive cannot and thus need not be explained; what is instinctive needs to be and thus ought to be expressed. Yet it is precisely in this interplay of culture and biology that the richest meaning of Gor lies concealed from Cabot.

Elinor Brinton, in the seventh volume, explores most fully the problematic relationship between the two forces, cultural overlay and biological instinct. She is not the first Earth woman - nor the most interesting nor the most intelligent - to leave the pampered life for the debasement of slavery on Gor. She finds it impossible to adjust to this culture which totally redefines her, even though her sensory threshold is changed radically, her appetite for food and her desire for men sharpened. She goes through the sequence which all the women in the chronicles pass through: she fears men, she hates men, she wants men; vanity yields to a conviction of inferiority, submission leads to love, subjugation intensifies the awareness of womanhood and thereby affords a real experience of freedom. It is by accepting caste, by identifying totally with social role, that the woman achieves fulfillment, freedom, totality. Everyone on Gor sooner or later agrees that only in male domination of the female can the woman create her own identity and, at the same time, paradoxically claim equality with the man. The sequence goes from princess to slavegirl to woman to wife in almost every treatment of ht eissue. The fulfilled woman transcends all the categories in her totality of fulfillment. This, Elizabeth Cardwell befriends an aristocratic freewoman and a slavegirl simultaneously; she is sold at auction standing between two kidnapped Earth women, one of whom hates men while the other desires a master. Elizabeth freely volunteers to act as slavegril and partner to Cabot in his assassin disguise in order to prove that women are equal to men in bravery. Elinor does not learn the lesson so easily. Only after she is branded, whipped and caged can she be traumatized into playing her social role.

Paradoxically, then, the prior role assigned by a prior culture resists transformation into the present role assigned by the present culture until the surrender to the present cultural role is effected by conditioning the reflexes and the power of biological instinct is released massively. Every women portrayed in the series demands at one point or another to be enslaved, to only possible means for archieving fulfillment and release. The warrior must learn his code so that he can act out his role; the slavegirl acts out her role so that she can learn her definition. The man discovers manliness in acting like a man; the woman discovers womanliness by accepting herself as a woman.

Cabot has the experience of hearing a woman demand to be enslaved in every novel in which he has the major role; he never understand why. He abhors the institution of slavery, and yet he can see some kind of biological advantage in the system. Although he does not believe fully in the idea, he fully enjoys the pleasures it offers him. He cannot reconcile his old Earth identity with his new social role on Gor.

Cabot never fully understands his own violence. He hates his father-in-law Marlenus because the dictator believes that only through the sowrd and guile can justice be secured, yet Cabot restores Marlenus to imperial power and duplicates that ruthlessness while acting as dictator of a pirates' haven. He hates the Machiavellian Priest-King Sarm and loves the sentimental Misk, yet in the war at the mountain caverns it is Cabot and Sarm who match themselves against one another while Misk stands passively aside. At the victory orgy which celebrates his success as a pirate, Cabot is told that his face now resembles that of the brutish captain whom he had killed at the outset of his career as a pirate. Only in the first novel does Cabot function as a soldier: elsewhere, he becomes an exaggeration of violence as an outlaw, an assassin, a buccaneer. In each novel he engages in a distinct kind of warfare: the siege, the revolution, guerrilla tactics, cavalry assaults, commando raids, war at sea, war in the sky. The two castes whom Cabot resents the most are the priests and the merchants, for they cannot be relied upon to add anything to the practical growth of society. Yet Cabot is himslef not a constructive force in society, but simply and unabashedly disruptive and destructive.

This inability to see himself from any angle but the purely subjective is a failure to transcend himself, and Cabot testifies to this failure by his lack of a sense of humor. The only wit he shows is in teasing slavegirls or in taunting his foils as they lie dying. Often enough, he is the butt of the banter, especially among the wold herders of the Mongol-like wagon people. When he tries to demonstrate to two robotlike figures in the mountain caverns of the Priest-Kings what it means to be human by dipping a moving transportation-disk audaciously, they believe that being human means acting foolishly. When Cabot disgraces himself in his own eyes among the marsh dwellers, he plunges into the worst cruelties as a distraction while deliberately tormenting a helpless slavegirl as the scapegoat of his conscience.

This intensity with which Cabot's mind is imprisoned within his own ego is demonstrated with remarkable subtlety in the first three volumes of the series. Close reading of alomst any passage will reveal that Cabot's perceptions are concentrated, not in sight or hearing as one might expect, but in the senses of touch and kinesthetics. His awareness of the world is centered on hot and cold, soft and hard, the tone of his muscles, organs. He seems obsessed with the psychosomatic. He observes the world and interprets it by his fingertips and the nerve endings in his gut. A recurrent motif in the novels is Cabot's entrapment underground in a setting so claustrophobic that it is smothering. This kinesthetic-tactile concentration is very clearly dramatized in the second volume, by the abrupt shift Cabot experiences in going from his paean of joy while soaring through the open air on tarnsback to his crushing confinement in the pits of the silver-mine.

Cabot commenly feels that the world is closing in on him; he is always exultant when givin the chance to burst into energetic motion. Pattern disturbs him; whether he is lassoing a slavegirl in a betting match, duelling a squad of gladiators, or attacking an enemy fleet at sea, Cabot studies the opponent's patterns so that he may break the patterns. He wins by isolating his opponent to perposeless movements uncoordinated with the group.

Gor is counterpoised and couterbalanced with Earth, but it stays hidden from sight behind the sun. Upon that secret world there is a social structure of elemental and barbaric resonances. The social structure reflects the biological process over which it has been raised, and in turn it engenders the rediscovery of instinct by those whose lives it shapes. Tarl Cabot describes this world, narrates his adventures in it, tries to evaluate it for the reader. But he never grasps its meaning: when he discussess the language of Gor he never penetrates intro grammer so as to seize hold of relationships, he merely gives word-for-word equivalencies between individual items of the Gorean and the English vocabularies. Because purpose and causal sequence elude him, he never understands his own purpose on Gor. He reveals more than he knows, however, so that his reader is less a stranger to the structures of Gor than he is. The reader comprehends Cabot within the framwork of Gor, while Cabot fails to comprehend Gor within the framework of his subjective confinement. Cabot presents himself, therefor, lagely as a fool, and John norman's chronicles of the counterearth stand revealed as a masterful exercise in irony.

Full Size Covers

Full Size Covers

This page is copyright © 2000/2013 by Simon van Meygaarden & Jon Ard - All Rights Reserved

This page is copyright © 2000/2013 by Simon van Meygaarden & Jon Ard - All Rights Reserved