|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

SILVER EDITION

|

|

SILVER EDITION |

|

Publication History

Cover Overview |

Reviews and Previews

Chapter Overview |

Word Cloud

[NEW]

First Chapter Preview [NEW] |

Cover Gallery (year)

Cover Gallery (edition) |

Cover Overview

Cover Overview

Reviews and Previews

Reviews and PreviewsHere is an overview of the 22 chapters in Marauders of Gor:

|

1. The Hall

2. The Temple of Kassau 3. I Make the Acquaintance of Ivar Forkbeard and Book Passage on His Ship 4. The Forkbeard and I Return to Our Game 5. Feed Her on the Gruel of Bond-maids 6. Ivar Forkbeard's Long Hall 7. The Kur 8. Hilda of Scagnar 9. The Forkbeard Will Attend The Thing 10. A Kur Will Address The Thing 11. The Torvaldsberg |

12. Ivar Forkbeard Introduces Himself to Svein Blue Tooth

13. Visitors in the Hall of Svein Blue Tooth 14. The Forkbeard and I Depart From the Hall of Svein Blue Tooth 15. On the Height of Torvaldsberg 16. The War Arrow 17. Torvaldslanders Visit the Camp of Kurii 18. What Then Occurred in the Camp of the Kurii 19. The Note 20. What Occurred on the Skerry of Vars 21. I Drink to the Honor of Tyros 22. I Take Ship from the North |

Word Cloud

Word CloudThe image below shows the most often used words and terms within Marauders of Gor. The larger the size, the more often the word or term occurs in the text.

First Chapter Preview

First Chapter Preview

1

The Hall

I sat alone in the great hall, in the darkness, in the Captain's Chair.

The walls of stone, some five feet in thickness, formed of large blocks, loomed about me. Before me, over the long, heavy table behind which I sat, I could see the large tiles of the hall floor. The table was now dark, and bare. No longer was it set with festive yellow and scarlet cloths, woven in distant Tor; no longer did it bear the freight of plates of silver from the mines of Tharna, nor of cunningly wrought goblets of gold from the smithies of luxurious Turia, Ar of the south. It was long since I had tasted the fiery paga of the Sa-Tarna fields north of the Vosk. Now, even the wines from the vineyards of Ar seemed bitter to me.

I looked up, at the narrow apertures in the wall to my right. Through them I could see certain of the stars of Gor, in the tarn-black sky.

The hall was dark. No longer did the several torches, bristling and tarred, burn in the iron rings at the wall. The hall was silent. No musicians played; no cup companions laughed and drank, lifting their goblets; on the broad, flat tiles before me, under the torches, barefoot, collared, in scarlet silks, bells at their wrists and ankles, there danced no slave girls.

The hall was large, and empty and silent. I sat alone.

Seldom did I have my chair carried from the hall. I remained much in this place.

I heard footsteps approaching. I did not turn my head. It caused me pain to do so.

"Captain," I heard.

It was Luma, the chief scribe of my house, in her blue robe and sandals. Her hair was blond and straight, tied behind her head with a ribbon of blue wool, from the bounding Hurt, dyed in the blood of the Vosk sorp. She was a scrawny girl, not attractive, but with deep eyes, blue; and she was a superb scribe, in her accounting swift, incisive, accurate, brilliant; once she had been a paga slave, though a poor one; I had saved her from Surbus, a captain, who had purchased her to slay her, she not having served him to his satisfaction in the alcoves of the tavern; he would have cast her, bound, to the swift, silken urts in the canals. I had dealt Surbus his death blow, but, before he had died, I had, on the urging of the woman, she moved to pity, carried him to the roof of the tavern, that he might, before his eyes closed, look once more upon the sea. He was a pirate, and a cutthroat, but he was not unhappy in his death; he had died by the sword, which would have been his choice, and before he had died he had looked again upon gleaming Thassa; it is called the death of blood and the sea; he died not unhappy; men of Port Kar do not care to die in their beds, weak, lingering, at the mercy of tiny foes that cannot see; they live often by violence and desire that they shall similarly perish; to die by the sword is regarded as the right, and honor, of he who lives by it.

"Captain," said the woman, standing back, to one side of the chair.

After the death of Surbus, the woman had been mine. I had won her from him by sword right. I had, of course, as she had expected, put her in my collar, and kept her slave. To my astonishment, however, by the laws of Port Kar, the ships, properties and chattels of Surbus, he having been vanquished in fair combat and permitted the death of blood and sea, became mine; his men stood ready to obey me; his ships became mine to command; his hall became my hall, his riches mine, his slaves mine. It was thus that I had become a captain in Port Kar, jewel of gleaming Thassa.

"I have the accounts for your inspection," said Luma.

Luma no longer wore her collar. After the victory of the 25th of Se'Kara, over the fleets of Tyros and Cos, I had freed her. She had much increased my fortunes. Freed, she took payment, but not as much as her services, I knew, warranted. Few scribes, I expected, were so skilled in the supervision and management of complex affairs as this slight, unattractive, brilliant girl. Other captains, other merchants, seeing the waxing of my fortunes, and understanding the commercial complexities involved, had offered this scribe considerable emoluments to join their service. She, however, had refused to do so. I expect she was pleased at the authority, and the trust and freedom, which I accorded her. Too, perhaps, she had grown fond of the house of Bosk.

"I do not wish to see the accounts," I told her.

"The Venna and Tela have arrived from Scagnar," she said, "with full cargoes of the fur of sea sleen. My information indicates that highest prices currently for such products are being paid in Asperiche."

"Very well," I said, "give the men time for their pleasures, eight days, and have the cargoes transferred to one of my round ships, whichever can be most swiftly fitted, and embark them for Asperiche, the Venna and Tela as convoy."

"Yes, Captain," said Luma.

"Go now," I said. "I do not wish to see the accounts."

"Yes, Captain," she said.

At the door, she stopped. "Does the captain wish food or drink?" she asked.

"No," I told her.

"Thurnock," she said, "would be pleased should you play with him a game of Kaissa."

I smiled. Huge, yellow-haired Thurnock, he of the peasants, master of the great bow, wished to play Kaissa with me. He knew himself no match for me in this game.

"Thank Thurnock for me," said I, "but I do not wish to play."

I had not played Kaissa since my return from the northern forests.

Thurnock was a good man, a kind man. The yellow-haired giant meant well.

"The accounts," said Luma, "are excellent. Your enterprises are prospering. You are much richer."

"Go," said I, "Scribe. Go, Luma."

She left.

I sat alone in the darkness. I did not wish to be disturbed.

I looked about the hall, at the great walls of stone, the long table, the tiles, the narrow apertures through which I could glimpse the far stars, burning in the scape of the night.

I was rich. So Luma said, so I knew. I smiled bitterly. There were few men as helpless, as impoverished as I. It was true that the fortunes of the house of Bosk had waxed mightily. I supposed there were few merchants in known Gor whose houses were as rich, as powerful, as mine. Doubtless I was the envy of men who did not know me, Bosk, the recluse, who had returned crippled from the northern forests.

I was rich. But I was poor, because I could not move the left side of my body.

Wounds had I at the shore of Thassa, high on the coast, at the edge of the forests, when one night I had, in a stockade of enemies, commanded by Sarus of Tyros, chosen to recollect my honor.

Never could I regain my honor, but I had recollected it. And never had I forgotten it.

Once I had been Tarl Cabot, in the songs called Tarl of Bristol. I recalled that I, or what had once been I, had fought at the siege of Ar. That young man with fiery hair, laughing, innocent, seemed far from me now, this huddled mass, half paralyzed, bitter, like a maimed larl, sitting alone in a captain's chair, in a great darkened hall. My hair was no longer now the same. The sea, the wind and the salt, and, I suppose, the changes in my body, as I had matured, and learned with bitterness the nature of the world, and myself, and men, had changed it. It was now, I thought, not much different from that of other men, as I had learned, too, that I was not much different, either, from others. It had turned lighter now, and more straw colored. Tarl Cabot was gone. He had fought in the siege of Ar. One could still hear the songs. He had restored Lara, Tatrix of Tharna, to her throne. He had entered the Sardar and was one of the few men who knew the true nature of Priest-Kings, those remote and extraordinary beings who controlled the world of Gor. He had been instrumental in the Nest War, and had earned the friendship and gratitude of the Priest-King, Misk, glorious, gentle Misk. "There is Nest Trust between us," Misk had told him. I recalled that once I, in the palms of my hands, had felt the delicate touch of the antennae of that golden creature. "Yes, there is Nest Trust between us," Tarl Cabot had told him. And he had gone to the Land of the Wagon Peoples, to the Plains of Turia, and had obtained there the last egg of Priest-Kings and had returned it, safe, to the Sardar. He had well served Priest-Kings, had Tarl Cabot, that young, brave, distant man, so fine, so proud, so much of the warriors. And he had gone, too, to Ar, and there had defeated the schemes of Cernus and the hideous aliens, the Others, intent upon the conquest of Gor, and then of Earth. He had well served Priest-Kings, that young man. And then he had ventured to the delta of the Vosk, to make his way through it, to make contact with Samos of Port Kar, agent of Priest-Kings, to continue in their service. But in the delta of the Vosk he had lost his honor. He had betrayed his codes. There, merely to save his miserable life, he had chosen ignominious slavery to the freedom of honorable death. He had sullied the sword, the honor, which he had pledged to Ko-ro-ba's Home Stone. By that act he had cut himself away from his codes, his vows. For such an act there was no atonement, even to the throwing of one's body upon one's own sword. It was in that moment of his surrender to his cowardice that Tarl Cabot had gone, and, in his place, knelt a slave contemptuously named Bosk, for a great, shambling oxlike creature of the plains of Gor.

But this Bosk, forcing his mistress, the beautiful Telima, to grant him his freedom, had come to Port Kar, bringing her with him as his slave, and had there, after many adventures, earned riches and fame, and the title even of Admiral of Port Kar. He stood high in the Council of Captains. And was it not he who had been victor on the 25th of Se'Kara, in the great engagement of the fleets of Port Kar and Cos and Tyros? He had come to love Telima, and had freed her, but she, when he had learned the location of his former Free Companion, Talena, once daughter of Marlenus of Ar, and resolved to free her from slavery, had left him, in the fury of a Gorean female, and had returned to the rence marshes, her home in the Vosk's vast delta.

A true Gorean, he knew, would have gone after her, and brought her back in slave bracelets and a collar. But he, in his weakness, had wept, and let her go.

Doubtless she despised him now in the marshes.

And so, Tarl Cabot gone, Bosk, Merchant of Port Kar, had gone to the northern forests, to free Talena, once his Free Companion.

There he had encountered Marlenus of Ar, Ubar of Ar, Ubar of Ubars. He, though only of the Merchants, had saved Marlenus of Ar from the degradation of slavery. That one such as he had been of service to the great Marlenus of Ar doubtless was tantamount to insult. But Marlenus had been freed. Earlier he had disowned his daughter, Talena, for she had sued for her freedom, a slave's act. His honor had been kept. That of Tarl Cabot could not be recovered.

But I recalled that I had, in the stockade of Tyros, recollected the matter of honor. I had entered the stockade alone, not expecting to survive. It was not that I was the friend of Marlenus of Ar, or his ally. It was rather that I had, as a warrior, or one once of such a caste, set myself the task of his liberation.

I had accomplished this task. And, in the night, under the stars, I had recollected a never-forgotten honor.

But wounds had I to show for this act, and a body heavy with pain, whose left side I could not move.

I had recollected my honor, but it had won for me only the chair of a cripple. To be sure, carved in wood, high on the chair, was the helmet with crest of sleen fur, the mark of the captain, but I could not rise from the chair.

My own body, and its weakness, held me, as chains could not.

Proud and mighty as the chair might be, it was the throne only of the maimed remains of a man.

I was rich!

I gazed into the darkness of the hall.

Samos of Port Kar had purchased Talena, as a mere slave, from two panther girls, obtaining her with ease in this manner while I had risked my life in the forest.

I laughed.

But I had recollected my honor. But little good had it done me. Was honor not a sham, a fraud, an invention of clever men to manipulate their less wily brethren? Why had I not returned to Port Kar and left Marlenus to his fate, to slavery, and doubtless, eventually, to a slave's death, broken and helpless, under the lashes of overseers in the quarries of Tyros?

I sat in the darkness and wondered on honor, and courage. If they were shams, I thought them most precious shams. How else could we tell ourselves from urts and sleen? What distinguishes us from such beasts? The ability to multiply and subtract, to tell lies, to make knives? No, I think particularly it is the sense of honor, and the will to hold one's ground.

But I had no right to such thoughts, for I had surrendered my honor, my courage, in the delta of the Vosk. I had behaved as might have any animal, not a man.

I could not recover my honor, but I could, and did upon one occasion, recollect it, in a stockade at the shore of Thassa, at the edge of the northern forests.

I grew cold in the blankets. I had become petulant, bitter, petty, as an invalid, frustrated and furious at his own weakness, does.

But when I, half paralyzed and crippled, had left the shore of Thassa I had left behind me a beacon, a mighty beacon formed from the logs of the stockade of Sarus, and it had blazed behind me, visible for more than fifty pasangs at sea.

I did not know why I had set the beacon, but I had done so.

It had burned, long and fiery in the Gorean night, on the stones of the beach, and then, in the morning it would have been ashes, and the winds and rains would have scattered them, and there would be little left, save the stones, the sand and the prints of the feet of sea birds, tiny, like the thief's brand, in the sand. But it would once have burned, and that was fixed, undeniable, a part of what had been, that it had burned; nothing could change that, not the eternities of time, not the will of Priest-Kings, the machinations of Others, the willfulness and hatred of men; nothing could change that it had been, that once on the beach, there, a beacon had burned.

I wondered how men should live. In my chair I had thought long on such matters.

I knew only that I did not know the answer to this question. Yet it is an important question, is it not? Many wise men give wise answers to this question, and yet they do not agree among themselves.

Only the simple, the fools, the unreflective, the ignorant, know the answer to this question.

Perhaps to a question this profound the answer cannot be known. Perhaps it is a question too deep to be answered. Yet we do know there are false answers to such a question. This suggests that there may be a true answer, for how can there be falsity without truth?

One thing seems clear to me, that a morality which produces guilt and self-torture, which results in anxiety and agony, which shortens life spans, cannot be the answer.

Many of the competitive moralities of Earth are thus mistaken.

But what is not mistaken?

The Goreans have very different notions of morality from those of Earth.

Yet who is to say who is the more correct?

I envy sometimes the simplicities of those of Earth, and those of Gor, who, creatures of their conditioning, are untroubled by such matters, but I would not be as either of them. If either should be correct it is for them no more than a lucky coincidence. They would have fallen into truth, but to take truth for granted is not to know it. Truth not won is not possessed. We are not entitled to truths for which we have not fought.

Do we not learn to live by doing, as we learn to speak by speaking, to paint by painting, to build by building?

Those who know best how to live, sometimes it seems to me, are those least likely to be articulate in such skills. It is not that they have not learned but, having learned, they find they cannot tell what they know, for only words can be told, and what is learned in living is more than words, other than words, beyond words. We can say, "This building is beautiful," but we do not learn the beauty of the building from the words; the building it is which teaches us its beauty; and how can one speak the beauty of the building, as it is? Does one say that it has so many pillars, that it has a roof of a certain type, and such? Can one simply say, "The building is beautiful"? Yes, one can say that but what one learns when one sees the beauty of the building cannot be spoken; it is not words; it is the building's beauty.

The morality of Earth, from the Gorean point of view, is a morality which would be viewed as more appropriate to slaves than free men. It would be seen in terms of the envy and resentment of inferiors for their superiors. It lays great stress on equalities and being humble and being pleasant and avoiding friction and being ingratiating and small. It is a morality in the best interest of slaves, who would be only too eager to be regarded as the equals of others. We are all the same. That is the hope of slaves; that is what it is in their interest to convince others of. The Gorean morality on the other hand is more one of inequalities, based on the assumption that individuals are not the same, but quite different in many ways. It might be said to be, though this is oversimple, a morality of masters. Guilt is almost unknown in Gorean morality, though shame and anger are not. Many Earth moralities encourage resignation and accommodation; Gorean morality is bent more toward conquest and defiance; many Earth moralities encourage tenderness, pity and gentleness, sweetness; Gorean morality encourages honor, courage, hardness and strength. To Gorean morality many Earth moralities might ask, "Why so hard?" To these Earth moralities, the Gorean ethos might ask, "Why so soft?"

I have sometimes thought that the Goreans might do well to learn something of tenderness, and, perhaps, that those of Earth might do well to learn something of hardness. But I do not know how to live. I have sought the answers, but I have not found them. The morality of slaves says, "You are equal to me; we are both the same"; the morality of masters says, "We are not equal; we are not the same; become equal to me; then we will be the same." The morality of slaves reduces all to bondage; the morality of masters encourages all to attain, if they can, the heights of freedom. I know of no prouder, more self-reliant, more magnificent creature than the free Gorean, male or female; they are often touchy, and viciously tempered, but they are seldom petty or small; moreover they do not hate and fear their bodies or their instincts; when they restrain themselves it is a victory over titanic forces; not the consequence of a slow metabolism; but sometimes they do not restrain themselves; they do not assume that their instincts and blood are enemies and spies, saboteurs, in the house of themselves; they know them and welcome them as part of their persons; they are as little suspicious of them as the cat of its cruelty, or the lion of its hunger; their desire for vengeance, their will to speak out and defend themselves, their lust, they regard as intrinsically and gloriously a portion of themselves as their hearing or their thinking. Many Earth moralities make people little; the object of Gorean morality, for all its faults, is to make people free and great. These objectives are quite different it is clear to see. Accordingly, one would expect that the implementing moralities would, also, be considerably different.

I sat in the darkness and thought on these things. There were no maps for me.

I, Tarl Cabot, or Bosk of Port Kar, was torn between worlds.

I did not know how to live.

I was bitter.

But the Goreans have a saying, which came to me in the darkness, in the hall. "Do not ask the stones or the trees how to live; they cannot tell you; they do not have tongues; do not ask the wise man how to live, for, if he knows, he will know he cannot tell you; if you would learn how to live do not ask the question; its answer is not in the question but in the answer, which is not in words; do not ask how to live, but, instead, proceed to do so."

I do not fully understand this saying. How, for example, can one proceed to do what one does not know how to do? The answer, I suspect, is that the Gorean belief is that one does, truly, in some way, know how to live, though one may not know that one knows. The knowledge is regarded as being somehow within one. Perhaps it is regarded as being somehow innate, or a function of instincts. I do not know. The saying may also be interpreted as encouraging one to act, to behave, to do, and then, in the acting, the doing, the behaving, to learn. These two interpretations, of course, are not incompatible. The child, one supposes, has the innate disposition, when a certain maturation level is attained, to struggle to its feet and walk, as it did to crawl, when an earlier level was attained, and yet it truly learns to crawl, and to walk, and then to run, only in the crawling, in the walking and running.

The refrain ran through my mind. "Do not ask how to live, but, instead, proceed to do so."

But how could I live, I, a cripple, huddled in the chair of a captain, in a darkened hall?

I was rich, but I envied the meanest herder of verr, the lowest peasant scattering dung in his furrows, for they could move as they pleased.

I tried to clench my left fist. But the hand did not move.

How should one live?

In the codes of the warriors, there is a saying: "Be strong, and do as you will. The swords of others will set you your limits."

I had been one of the finest swordsmen on Gor. But now I could not move the left side of my body.

But I could still command steel, that of my men, who, for no reason I understood, they Goreans, remained true to me, loyal to a cripple, confined to a captain's chair in a darkened hall.

I was grateful to them, but I would show them nothing of this, for I was a captain.

They must not be demeaned.

"Within the circle of each man's sword," say the codes of the warrior, "therein is each man a Ubar."

"Steel is the coinage of the warrior," say the codes. "With it he purchases what pleases him."

When I had returned from the northern forests I had resolved not to look upon Talena, once daughter of Marlenus of Ar, whom Samos had purchased from panther girls.

But I had had my chair carried to his hall.

"Shall I present her to you," asked Samos, "naked, and in bracelets?"

"No," I had said. "Present her in the most resplendent robes you can find, as befits a high-born woman of the city of Ar."

"But she is a slave," he said. "Her thigh bears the brand of Treve. Her throat is encircled in the collar of my house."

"As befits," said I, "a high-born woman of the city of glorious Ar."

And so it was that she, Talena, once daughter of Marlenus of Ar, then disowned, once my companion, was ushered into my presence.

"The slave," said Samos.

"Do not kneel," I said to her.

"Strip your face, Slave," said Samos.

Gracefully the girl, the property of Samos, first slaver of Port Kar, removed her veil, unfastening it, dropping it about her shoulders.

We looked once more upon each other.

I saw again those marvelous green eyes, those lips, luscious, perfect for crushing beneath a warrior's mouth and teeth, the subtle complexion, olive. She removed a pin from her hair, and, with a small movement of her head, shook loose the wealth of her sable hair.

We regarded one another.

"Is master pleased?" she asked.

"It has been long, Talena," said I.

"Yes," she said, "it has been long."

"He is free," said Samos.

"It has been long, Master," she said.

"Many years," said I. "Many years." I smiled at her. "I last saw you on the night of our companionship."

"When I awakened, you were gone," she said. "I was abandoned."

"Not of my own free will did I leave you," said I. "That was not of my will."

I saw in the eyes of Samos that I must not speak of Priest-Kings. It had been they who had returned me then to Earth.

"I do not believe you," she said.

"Watch your tongue, Girl," said Samos.

"If you command me to believe you," she said, "I shall, of course, for I am slave."

I smiled. "No," I said, "I do not command you."

"I was kept in great honor in Ko-ro-ba," she said, "respected and free, for I had been your companion, even after the year of the companionship had gone, and it had not been renewed."

At that point, in Gorean law, the companionship had been dissolved. The companionship had not been renewed by the twentieth hour, the Gorean Midnight, of its anniversary.

"When Priest-Kings, by fire signs, made it clear Ko-ro-ba was to be destroyed, I left the city."

No stone would be allowed to stand upon a stone, no man of Ko-ro-ba to stand by another.

The population had been scattered, the city razed by the power of the Priest-Kings.

"You fell slave," I said.

"Within five days," she said, "as I tried to return to Ar, I was sheltered by an itinerant leather worker, who did not believe, of course, that I was the daughter of Marlenus of Ar. He treated me well the first evening, with gentleness and honor. I was grateful. In the morning, to his laughter, I awakened. His collar was on my throat." She looked at me, angrily. "He then used me well. Do you understand? He forced me to yield to him, I, the daughter of Marlenus of Ar, he only a leather worker. Afterwards he whipped me. He taught me to obey. At night he chained me. He sold me to a salt merchant." She regarded me. "I have had many masters," she said.

"Among them," I said, "Rask of Treve."

She stiffened. "I served him well," she said. "I was given no choice. It was he who branded me." She tossed her head. "Until then many masters had regarded me as too beautiful to brand."

"They were fools," said Samos. "A brand improves a slave."

She put her head in the air. I had no doubt this was one of the most beautiful women on Gor.

"It is because of you, I gather," said she to me, "that I have been permitted clothing for this interview. Further, I have you to thank, I gather, that I have been given the opportunity to wash the stink of the pens from my body."

I said nothing.

"The cages are not pleasant," she said. "My cage measures four paces by four paces. In it are twenty girls. Food is thrown to us from above. We drink from a trough."

"Shall I have her whipped?" asked Samos.

She paled.

"No," I said.

"Rask of Treve gave me to a panther girl in his camp, one named Verna. I was taken to the northern forests. My present master, noble Samos of Port Kar, purchased me at the shore of Thassa. I was brought to Port Kar chained to a ring in the hold of his ship. Here, in spite of my birth, I was placed in a pen with common girls."

"You are only another slave," said Samos.

"I am the daughter of Marlenus of Ar," she said, proudly.

"In the forest," I said, "it is my understanding that you sued for your freedom, begging in a missive that your father purchase you."

"Yes," she said. "I did so."

"Are you aware," I asked, "that against you, on his sword and on the medallion of Ar, Marlenus swore the oath of disownment?"

"I do not believe it," she said.

"You are no longer his daughter," I said. "You are now without caste, without Home Stone, without family."

"You lie!" she screamed.

"Kneel to the whip," said Samos.

Piteously she knelt, a slave girl. Her wrists were crossed under her, as though bound, her head was to the floor, the bow of her back was exposed.

She shuddered. I had little doubt but what this slave knew well, and much feared, the disciplining kiss of the Gorean slave lash.

Samos' sword was in his hand, thrust under the collar of her garment, ready to thrust in and lift, parting the garment, causing the robes to fall to either side, about her then naked body.

"Do not punish her," I told Samos.

Samos looked at me, irritably. The slave had not been pleasing.

"To his sandal, Slave," said Samos.

I felt Talena's lips press to my sandal. "Forgive me, Master," she whispered.

"Rise," I said.

She rose to her feet, and stepped back. I could see she feared Samos.

"You were disowned," I told her. "Your status now, whether you know this or not, is less than that of the meanest peasant wench, secure in her caste rights."

"I do not believe you," she said.

"Do you care for me," I asked, "Talena."

She pulled the robes down from her throat. "I wear a collar," she said. I saw the simple, circular, gray collar, the collar of the house of Samos, locked about her throat.

"What is her price?" I asked Samos.

"I paid ten pieces of gold for her," said Samos.

She seemed startled that she had sold for so small a sum. Yet, for a girl, late in the season, high on the coast of Thassa, it was a marvelous price. Doubtless she had obtained it only because she was so beautiful. Yet, to be sure, it was less than she would have brought if expertly displayed on the block in Turia or Ar, or Ko-ro-ba, or Tharna, or Port Kar.

"I will give you fifteen," I said.

"Very well," said Samos.

With my right hand I reached into the pouch at my belt and drew out the coins.

I handed them to Samos.

"Free her," I said.

Samos, with a general key, one used for many of the gray collars, unlocked the band of steel which encircled her lovely throat.

"Am I truly free?" she asked.

"Yes," I said.

"I should have brought a thousand pieces of gold," she said. "As the daughter of Marlenus of Ar my companion price might be a thousand tarns, five thousand tharlarion!"

"You are no longer the daughter of Marlenus of Ar," I told her.

"You are a liar," she said. She looked at me, contemptuously.

"With your permission," said Samos, "I shall withdraw."

"Stay," said I, "Samos."

"Very well," said he.

"Long ago," said I, "Talena, we cared for one another. We were companions."

"It was a foolish girl who cared for you," said Talena. "I am now a woman."

"You no longer care for me?" I asked.

She looked at me. "I am free," she said. "I can speak what I wish. Look at yourself! You cannot even walk. You cannot even move your left arm! You are a cripple, a cripple! You make me ill! Do you think that one such as I, the daughter of Marlenus of Ar, could care for such a thing? Look upon me. I am beautiful. Look upon yourself. You are a cripple. Care for you? You are a fool, a fool!"

"Yes," I said, bitterly, "I am a fool."

She turned away, robes swirling. Then she turned and faced me. "Slave!" she sneered.

"I do not understand," I said.

"I took the liberty," said Samos, "though at the time I did not know of your injuries, your paralysis, to inform her of what occurred in the delta of the Vosk."

My right hand clenched. I was furious.

"I am sorry," said Samos.

"It is no secret," I said. "It is known to many."

"It is a wonder that any man will follow you!" cried Talena. "You betrayed your codes! You are a coward! A fool! You are not worthy of me! That you dare ask me if I could care for such as you is to me, a free woman, an insult! You chose slavery to death!"

"Why did you tell her of the delta of the Vosk?" I asked Samos.

"So that if there might have been love between you, it would no longer exist," said Samos.

"You are cruel," I said.

"Truth is cruel," said Samos. "She would have to know sooner or later."

"Why did you tell her?" I asked.

"That she might not care for you and lure you from the service of those whose names we shall not now speak."

"I could never care for a cripple," said Talena.

"It remained yet my hope," said Samos, "to recall you to a lofty service, one dignified and of desperate importance."

I laughed.

Samos shrugged. "I did not know until too late the consequences of your wounds. I am sorry."

"Now," said I, "Samos, I cannot serve even myself."

"I am sorry," said Samos.

"Coward! Traitor to your codes! Sleen!" cried Talena.

"All that you say is true," I told her.

"You did well, I understand," said Samos, "in the stockade of Sarus of Tyros."

"I wish to be returned to my father," said Talena.

I drew forth five pieces of gold. "This money," said I to Samos, "is for safe passage to Ar, by guard and tarn, for this woman."

Talena drew about her face her veil, refastening it. "I shall have the moneys returned to you," she said.

"No," I said, "take it rather as a gift, as a token of a former affection, once borne to you by one who was honored to be your companion."

"She is a she-sleen," said Samos, "vicious and ignoble."

"My father would avenge that insult," she said, coldly, "with the tarn cavalries of Ar."

"You have been disowned," said Samos, and turned and left. I held still the five coins in my hand.

"Give me the coins," said Talena. I held them in my hand, in the palm. She came to me and snatched them away, as though loath to touch me. Then she stood and faced me, the coins in her hand. "How ugly you are," she said. "How hideous in your chair!"

I did not speak.

She turned and strode toward the door of the hall. At the portal she stopped, and turned. "In my veins," she said, "flows the blood of Marlenus of Ar. How revolting and incredible that one such as you, a coward and betrayer of codes, should have aspired to touch me." She lifted the coins in her hand. It was gloved. "My gratitude," said she, "Sir," and turned away.

"Talena?" I cried.

She turned to face me once more.

"It is nothing," I said.

"And you will let me go," she said. She smiled contemptuously. "You were never a man," she said. "Always you were a boy, a weakling." She lifted the coins again in her hand. "Farewell, Weakling," said she, and left the room.

I now sat in my own hall, in the darkness, thinking on many things.

I wondered how to live.

"Within the circle of each man's sword," say the codes of the warrior, "therein is each man a Ubar."

"Steel is the coinage of the warrior," say the codes. "With it he purchases what pleases him."

Once I had been among the finest swordsmen on the planet Gor. Now I was a cripple.

Talena would now be in Ar. How startled, how crushed would she have been, to learn at last, incontrovertibly, that her disownment was true. She had begged to be purchased, a slave's act. Marlenus, protecting his honor, on his sword and upon the medallion of the Ubar, had sworn her from him. No longer had she caste, no longer a Home Stone. The meanest peasant wench, secure in her caste rights, would be more than Talena. Even a slave girl has her collar. I knew that Marlenus would keep her sequestered in the central cylinder, that her shame not reflect upon his glory. She would be in Ar, in effect, a prisoner. She was no longer entitled even to call its Home Stone her own. Such an act, by one such as she, was subject to public discipline. For it she might be suspended naked, bound by the wrists, on a forty foot rope from one of the high bridges, to be lashed by tarnsmen, sweeping past her in flight.

I had watched her go.

I had not attempted to stop her.

And when Telima had fled my house, when I had determined to seek Talena in the northern forests, I had, too, let her go. I smiled. A true Gorean, I knew, would have followed her, and brought her back in bracelets and collar.

I thought then of Vella, once Elizabeth Cardwell, whom I had encountered in the city of Lydius, at the mouth of the Laurius River, below the borders of the forests. I had once loved her, and had wanted to return her safe to Earth. But she had not honored my will, but, that night, had saddled my tarn, great Ubar of the Skies, and fled the Sardar. When the bird had returned I, in fury, had driven it away. Then I had encountered the girl in a paga tavern in Lydius; she had fallen slave. Her flight had been a brave act. I admired her, but it was an act not without its consequences. She had gambled; she had lost. In an alcove, after I had used her, she had begged me to buy her, to free her. It was a slave's act, like that of Talena. I had left her slave in the paga tavern. Before I had left I had informed her master, Sarpedon of Lydius, that, as he did not know, she was an exquisitely trained pleasure slave, and a most stimulating performer of slave dances. I had not returned that night to see her dance in the sand to please his customers. I had matters of business to attend to. She had not honored my will. She was only a female. She had cost me a tarn.

She had told me that I had become harder, more Gorean. I wondered if it were true or not. A true Gorean, I speculated, would not have left her in the paga tavern. A true Gorean, I speculated, would have purchased her, and brought her back, to put her with his other women, a delicious new slave for his house. I smiled to myself. The girl Elizabeth Cardwell, once a secretary in New York City, was one of the most delicious little wenches I had ever seen in slave silk. Her thigh bore the brand of the four bosk horns.

No, I had not treated her as would have a true Gorean. I had not brought her back in my collar, to serve my pleasures.

And, too, I knew that I had, in the fevered delirium attendant on my wounds, when I lay in the stern castle of the Tesephone, cried out her name.

This had shamed me, and was weakness. Though I was half motionless, though I could not close the fingers of my left hand, I resolved that I must burn from myself the vestiges of weakness. There was still much in me that was of Earth, much shallowness, much compromise, much weakness. I was not yet in my will truly Gorean.

I wondered how to live. "Do not ask how to live, but, instead, proceed to do so."

I wondered, too, on the nature of my affliction. I had had the finest wound physicians on Gor brought to attend me, to inquire into its nature. They could tell me little. Yet I had learned there was no damage in the brain, nor directly to the spinal column. The men of medicine were puzzled. The wounds were deep, and severe, and would doubtless, from time to time, cause me pain, but the paralysis, given the nature of the injury, seemed to them unaccountable.

Then one more physician, unsummoned, came to my door.

"Admit him," I had said.

"He is a renegade from Turia, a lost man," had said Thurnock.

"Admit him," I had said.

"It is Iskander," whispered Thurnock.

I knew well the name of Iskander of Turia. I smiled. He remembered well the city that had exiled him, keeping still its name as part of his own. It had been many years since he had seen its lofty walls. He had, in the course of his practice in Turia, once given treatment outside of its walls to a young Tuchuk warrior, whose name was Kamchak. For this aid given to an enemy he had been exiled. He had come, like many, to Port Kar. He had risen in the city, and had been for years the private physician of Sullius Maximus, who had been one of the five Ubars, presiding in Port Kar prior to the assumption of power by the Council of Captains. Sullius Maximus was an authority on poetry, and gifted in the study of poisons. When Sullius Maximus had fled the city, Iskander had remained behind. He had even been with the fleet on the 25th of the Se'Kara. Sullius Maximus, shortly after the decision of the 25th of Se'Kara, had sought refuge in Tyros, and had been granted it.

"Greetings, Iskander," I had said.

"Greetings, Bosk of Port Kar," he had said.

The findings of Iskander of Turia matched those of the other physicians, but, to my astonishment, when he had replaced his instruments in the pouch slung at his shoulder, he said, "The wounds were given by blades of Tyros."

"Yes," I said, "they were."

"There is a subtle contaminant in the wounds," he said.

"Are you sure?" I asked.

"I have not detected it," he said. "But there seems no likely alternative explanation."

"A contaminant?" I asked.

"Poison, I think," said he, "perhaps a subtle toxin, coated on a blade, thus entered into a wound."

"Such is contrary to the codes," I said.

"Poisoned steel," he said.

I said nothing.

"Sullius Maximus," he said, "is in Tyros."

"I would not have thought Sarus of Tyros would have used poisoned steel," I said. Such a device, like the poisoned arrow, was not only against the codes of the warriors, but, generally, was regarded as unworthy of men. Poison was regarded as a woman's weapon.

Iskander shrugged.

"Sullius Maximus," he said, "invented such a drug. He tested it, by pin pricks, on the limbs of a captured enemy, paralyzing him from the neck down. He kept him seated at his right side, as a guest in regal robes, for more than a week. When he tired of the sport he had him killed."

"Is there an antidote?" I asked.

"No," said Iskander.

"Then there is no hope," I said.

"No," said Iskander. "There is no hope."

"Perhaps it is not the poison," I said.

"Perhaps," said Iskander.

"Thurnock," said I, "give this physician a double tarn, of gold."

"No," said Iskander. "I wish no payment."

"Why not?" I asked.

"I was with you," he said, "on the 25th of Se'Kara."

"I wish you well, Physician," I said.

"I wish you well, too, Captain," said he, and left.

I wondered if what Iskander of Turia had conjectured was correct or not.

I wondered if such a poison, if it existed, could be overcome.

There is no antidote, he had informed me.

The refrain ran through my mind: "Do not ask how to live, but, instead, proceed to do so."

I laughed bitterly.

"Captain!" I heard. "Captain!" It was Thurnock. I could hear running feet behind him, the gathering of members of the household.

"What is it?" I heard Luma ask.

"Captain!" cried Thurnock.

"I must see him, immediately!" said another voice. I was startled. It was the voice of Samos, first slaver of Port Kar.

They entered, carrying torches.

"Put torches in the rings," said Samos.

The hall was lit. Members of the house came forward. Samos appeared before the table. At his side was Thurnock, a torch still uplifted in his hand. Luma was present. I saw, too, Tab, who was captain of the Venna. Clitus, too, was there, and young Henrius.

"What is wrong?" I asked.

Then one other stepped forward. It was Ho-Hak, from the marshes, the rencer. His face was white. No longer about his throat was clasped the collar of the galley slave, with short, dangling chain. He had been a bred slave, an exotic. His ears were large, bred so as a collector's fancy. But he had killed his master, breaking his neck, and escaped. Recaptured, he had been sentenced to the galleys, but had escaped, too, from them, killing six men in his flight. He had, finally, succeeded in making his way into the marshes, in the Vosk's vast delta, where he had been taken in by rencers, who live on islands, woven of rence reeds, in the delta. He had become chief of one such group, and was much respected in the delta. He had been instrumental in bringing the great bow to the rencers, which put them on a military par with those of Port Kar, who had thitherto victimized and exploited them. Rencer bowmen were now used by certain captains of Port Kar as auxiliaries.

Ho-Hak did not speak but cast on the table an armlet of gold.

It was bloodied.

I knew the armlet well. It had been that of Telima, who had fled to the marshes, when I had determined to seek Talena in the northern forests.

"Telima," said Ho-Hak.

"When did this happen?" I asked.

"Within four Ahn," said Ho-Hak. Then he turned to another rencer, one who stood with him. "Speak," said Ho-Hak.

"I saw little," he said. "There was a tarn and a beast. I heard the scream of the woman. I poled my rence craft toward them, my bow ready. I heard another scream. The tarn took flight, low, over the rence, the beast upon it, hunched, shaggy. I found her rence craft, the pole floating nearby. It was much bloodied. I found there, too, the armlet."

"The body?" I asked.

"Tharlarion were about," said the rencer.

I nodded.

I wondered if the beast had struck for hunger. Such a beast in the house of Cernus had fed on human flesh. Doubtless it was little other to them than venison would be to us.

It was perhaps just as well that the body was not recovered. It would have been half eaten, torn apart. It was just as well that the remains had been given to the tharlarion.

"Why did you not kill the beast, or strike the tarn?" I asked.

The great bow was capable of such matters.

"I had no opportunity," said the rencer.

"Which way did the tarn take flight?" I asked.

"To the northwest," said the rencer.

I was certain the tarn would follow the coast. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to fly a tarn from the sight of land. It is counterinstinctual for them. In the engagement of the 25th of Se'Kara we had used tarns at sea, but they had been kept below decks in cargo ships until beyond the sight of land. Interestingly, once released, there had been no difficulty in managing them. They had performed effectively in the engagement.

I looked at Samos. "What do you know of this matter?" I asked.

"I know only what I am told," said Samos.

"Describe the beast," I said to the rencer.

"I did not see it well," he said.

"It could only have been one of the Kurii," said Samos.

"The Kurii?" I asked.

"The word is a Gorean corruption of their name for themselves, for their kind," said Samos.

"In Torvaldsland," said Tab, "that word means 'beasts'."

"That is interesting," I said. If Samos were correct that 'Kurii' was a Gorean corruption of the name of such animals for themselves, and that the word was used in Torvaldsland as a designation for beasts, then it seemed not unlikely that such animals were not unknown in Torvaldsland, at least in certain areas, perhaps remote ones.

The tarn had flown northwest. It would, presumably, follow the coast north, perhaps above the forests, perhaps to the bleak coasts of forbidding Torvaldsland itself.

"Do you surmise, Samos," I asked, "that the beast killed for hunger?"

"Speak," said Samos to the rencer.

"The beast," he said, "had been seen earlier, twice, on abandoned, half-rotted rence islands, lurking."

"Did it feed?" I asked.

"Not on those of the marshes," said the man.

"It had opportunity?" I asked.

"As much or more as when it made its strike," said the man.

"The beast struck once, and once only?" I asked.

"Yes," said the man.

"Samos?" I asked.

"The strike," said Samos, "seems deliberate. Who else in the marshes wore a golden armlet?"

"But why?" I asked. "Why?"

He looked at me. "The affairs of worlds," said Samos, "apparently still touch you."

"He is crippled!" cried Luma. "You speak strangely! He can do nothing! Go away!"

I put down my head.

On the table I felt my fists clenched. I suddenly felt a hideous exhilaration.

"Bring me a goblet," I said.

A goblet was fetched. It was of heavy gold. I took it in my left hand. Slowly I crushed it.

I threw it from me.

Those of my house stood back, frightened.

"I will go," said Samos. "There is work to be done in the north. I will seek the vengeance."

"No, Samos," I said. "I will go."

There were gasps from those about.

"You cannot go," whispered Luma.

"Telima was once my woman," I said. "It is mine to seek the vengeance."

"You are crippled! You cannot move!" cried Luma.

"There are two swords over my couch," said I to Thurnock. "One is plain, with a worn hilt; the other is rich, with a jewel-encrusted hilt."

"I know them," whispered Thurnock.

"Bring to me the blade of Port Kar, swift, fit with inhilted jewels."

He sped from the room.

"I would have paga," I said. "And bring me the red meat of bosk."

Henrius and Clitus left the table.

The sword was brought. It was a fine blade. It had been carried on the 25th of Se'Kara. Its blade was figured, its hilt encrusted with jewels.

I took the goblet, filled with burning paga. I had not had paga since returning from the northern forests.

"Ta-Sardar-Gor," said I, pouring a libation to the table. Then I stood.

"He is standing!" cried Luma. "He is standing!"

I threw back my head and swilled down the paga. The meat, red and hot, was brought, and I tore it in my teeth, the juices running at the side of my mouth.

The blood and the paga were hot and dark within me. I felt the heat of the meat.

I threw from me the goblet of gold. I tore the meat and finished it.

I put over my left shoulder the scabbard strap.

"Saddle a tarn," said I to Thurnock.

"Yes, Captain," he whispered.

I stood before the captain's chair. "More paga," I said. Another vessel was brought. "I drink," said I, "to the blood of beasts."

Then I drained the goblet and flung it from me.

With a howl of rage I struck the table with the side of my fists, shattering the boards. I flung aside the blanket and the captain's chair.

"Do not go," said Samos. "It may be a trick to lure you to a trap."

I smiled at him. "Of course," I said. "To those with whom we deal Telima is of no importance." I regarded him. "It is me they want," I said. "They shall not fail to have their opportunity."

"Do not go," said Samos.

"There is work to be done in the north," I said.

"Let me go," said Samos.

"Mine," I said, "is the vengeance."

I turned and strode toward the door of the hall. Luma fell back before me, her hand before her mouth.

I saw that her eyes were deep, and very beautiful. She was frightened.

"Precede me to my couch," I said.

"I am free," she whispered.

"Collar her," I said to Thurnock, "and send her to my couch."

His hand closed on the arm of the thin blond scribe.

"Clitus," I said, "send Sandra, the dancer, to my couch as well."

"You freed her, Captain," smiled Clitus.

"Collar her," I told him.

"Yes, Captain," he said. I well remembered Sandra, with her black eyes, brownish skin and high cheekbones. I wanted her.

It had been long since I had had a woman.

"Tab," said I.

"Yes, Captain," said he.

"The two females," I told him, "have recently been free. Accordingly, as soon as they are collared, force them to drink slave wine."

"Yes, Captain," grinned Tab.

Slave wine is bitter, intentionally so. Its effect lasts for more than a Gorean month. I did not wish the females to conceive. A female slave is taken off slave wine only when it is her master's intention to breed her.

"The tarn, Captain?" asked Thurnock.

"Have it saddled," I told him. "I leave shortly for the north."

"Yes, Captain," he said.

Cover Gallery (year)

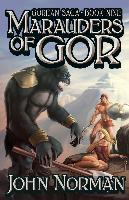

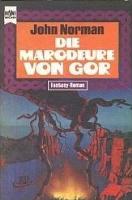

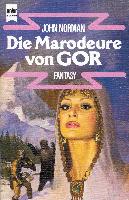

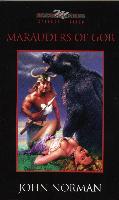

Cover Gallery (year)Here is a cover gallery showing all the editions and printings of Marauders of Gor, sorted by year of publication. Click on any cover to see the book.

Cover Gallery (edition)

Cover Gallery (edition)Here is a cover gallery showing all the editions and printings of Marauders of Gor, sorted by edition. Click on any cover to see the book.

This page is copyright © 2000/2013 by Simon van Meygaarden & Jon Ard - All Rights Reserved

This page is copyright © 2000/2013 by Simon van Meygaarden & Jon Ard - All Rights Reserved