|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

SILVER EDITION

|

|

SILVER EDITION |

|

Publication History

Cover Overview |

Reviews and Previews

Chapter Overview |

Word Cloud

[NEW]

First Chapter Preview [NEW] |

Cover Gallery (year)

Cover Gallery (edition) |

Cover Overview

Cover Overview

Reviews and Previews

Reviews and Previews Chapter Overview

Chapter OverviewHere is an overview of the 19 chapters in Savages of Gor:

|

1. Kog and Sardak; The Parley in the Delta

2. I Will Go to the Barrens 3. I Receive Information; I Will Travel Northward 4. We See Smoke; We Encounter Soldiers 5. I Throw Stones on the Road to Kailiauk 6. Kailiauk 7. Ginger 8. Grunt 9. We Cross the Ihanke 10. I See Dust Behind Us |

11. Slave Instruction; It Seems We Are No Longer Being Followed

12. I Learn Why We Are No Longer Being Followed; We Add Two Members to our Party 13. Blankets and Bonds; I Do a Favor for Grunt 14. It is a Good Trading; Pimples; I Learn Something of the Waniyanpi; Corn Stalks; Sign; Grunt and I Will Proceed East 15. The Fleer 16. The Kur; I Meet Waniyanpi; I Hear of the Lady Mira 17. The Slave 18. Cuwignaka; Sleen, Yellow Knives and Kaiila 19. In the Distance There is the Smoke of Cooking Fires |

Word Cloud

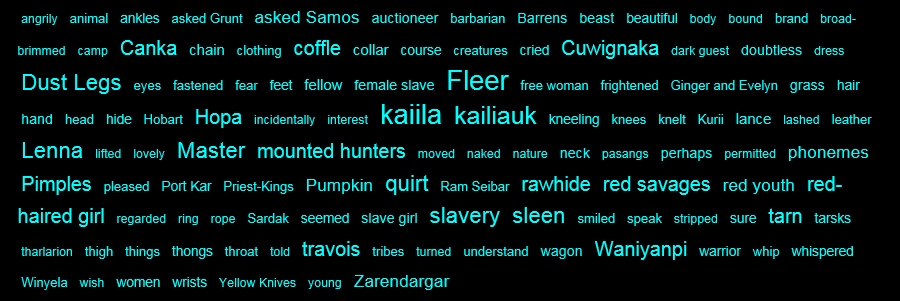

Word CloudThe image below shows the most often used words and terms within Savages of Gor. The larger the size, the more often the word or term occurs in the text.

First Chapter Preview

First Chapter Preview

1

Kog and Sardak;

The Parley in the Delta

"How many are there?" I asked Samos.

"Two," he said.

"Are they alive?" I asked.

"Yes," he said.

At the second Ahn, long before dawn, the herald of Samos had come to the lakelike courtyard of my holding in many-canaled Port Kar, that place of many ships, scourge of Thassa, that dark jewel in her gleaming green waters. Twice had he struck on the bars of the sea gate, each time with the Ka-la-na shaft of his spear, not with the side of its broad tapering bronze point. The signet ring of Samos of Port Kar, first captain of the council of captains, was displayed. I would be roused. The morning, in early spring, was chilly.

"Does Tyros move?" I asked blond-haired Thurnock, that giant of a man, he of the peasants, who had come to rouse me.

"I think not, Captain," said he.

The girl beside me pulled the furs up about her throat, frightened.

"Have ships of Cos been sighted?" I asked.

"I do not think so, Captain," said he.

There was a sound of chain beside me. The chain had moved against the collar ring of the girl beside me. Beneath the furs she was naked. The chain ran from the slave ring at the foot of my couch, a heavy chain, to the thick metal collar fastened on her neck.

"It is not, then, on the business of Port Kar that he comes?" I had asked.

"I think perhaps not, Captain," said Thurnock. "I think that the matters have to do with business other than that of Port Kar."

The small tharlarion-oil lamp he held illuminated his bearded face as he stood near the door.

"It has been quiet," I said, "for too long."

"Captain?" he asked.

"Nothing," I said.

"It is early," whispered the girl next to me.

"You were not given permission to speak," I told her.

"Forgive me, Master," she said.

I threw back the heavy furs on the great stone couch. Quickly the girl pulled up her legs and turned on her side. I, sitting up, looked down at her, trying to cover herself from the sight of Thurnock. I pulled her then beneath me. "Ohh," she breathed.

"You will grant him, then, an audience?" asked Thurnock.

"Yes," I said.

"Oh," said the girl. "Ohh!"

Now, as she lay, the small, fine brand high on her left thigh, just below the hip, could be seen. I had put it there myself, at my leisure, once in Ar.

"Master, may I speak?" she begged.

"Yes," I said.

"One is present," she said. "Another is present!"

"Be silent," I told her.

"Yes, my Master," she said.

"You will be there shortly?" asked Thurnock.

"Yes," I told him. "Shortly."

The girl looked wildly over my shoulder, toward Thurnock. Then she clutched me, her eyes closed, shuddering, and yielded. When again she looked to Thurnock she did so as a yielded slave girl, pinned in my arms.

"I shall inform the emissary of Samos that you will be with him in moments," said Thurnock.

"Yes," I told him.

He then left the room, putting the small tharlarion-oil lamp on a shelf near the door.

I looked down into the eyes of the girl, held helplessly in my arms.

"What a slave you made me," she said.

"You are a slave," I told her.

"Yes, my Master," she said.

"You must grow accustomed to your slavery, in all its facets," I told her.

"Yes, my Master," she said.

I withdrew from her then, and sat on the edge of the couch, the furs about me.

"A girl is grateful that she was touched by her Master," she said.

I did not respond. A slave's gratitude is nothing, as are slaves.

"It is early," she whispered.

"Yes," I said.

"It is very cold," she said.

"Yes," I said. The coals in the brazier to the left of the great stone couch had burned out during the night. The room was damp, and cold, from the night air, and from the chill from the courtyard and canals. The walls, of heavy stone, too, saturated with the chilled, humid air, would be cold and damp, and the defensive bars set in the narrow windows, behind the buckled leather hangings. On my feet I could feel the dampness and moisture on the tiles. I did not give her permission to draw back under the covers, nor was she so bold or foolish as to request that permission. I had been lenient with her this night. I had not slept her naked on the tiles beside the couch, with only a sheet for warmth, nor naked at the foot of the couch, with only a chain for comfort.

I rose from the couch and went to a bronze basin of cold water at the side of the room. I squatted beside it and splashed the chilled water over my face and body.

"What does it mean, my Master," asked the girl, "that one from the house of Samos, first captain in Port Kar, comes so early, so secretly, to the house of my Master?"

"I do not know," I said. I toweled myself dry, and turned to look upon her. She lay on her left elbow, on the couch, the chain running from her collar to the surface of the couch, and thence to the slave ring fixed deeply in its base. Seeing my eyes upon her she then knelt on the surface of the couch, kneeling back on her heels, spreading her knees, straightening her back, lifting her head, and putting her hands on her thighs. It is a common kneeling position for a female slave.

"If you knew, you would not tell me, would you?" she asked.

"No," I said.

"I am a slave," she said.

"Yes," I said.

"You had me well," she said, "and as a slave."

"It is fitting," I said.

"Yes, Master," she said.

I then returned to the couch, and sat upon its edge. She then left the couch, that she might kneel on the tiles before me. I looked down at her. How beautiful are enslaved women.

"Perhaps," I said, "you might speculate on what business brings the emissary of Samos of Port Kar to my house this morning?"

"I, Master?" she asked, frightened.

"Yes," I said. "You once served Kurii, the Others, the foes of Priest-Kings."

"I told all that I knew," she exclaimed. "I told all in the dungeons of Samos! I was terrified! I held back nothing! I was emptied of information!"

"You were then valueless," I said.

"Except, perhaps, as I might please a man as a slave," she said.

"Yes," I smiled.

Samos himself had issued the order of enslavement on her. In Ar I had presented the document to her and shortly thereafter, as it pleased me, implemented its provisions. She had once been Miss Elicia Nevins, of Earth, an agent of Kurii on Gor. Then, in Ar, a city from which once I had been banished, I had caught and enslaved her. In those compartments which had been her own in Ar she had become my capture, and had been stripped and placed in my bonds. In her own compartments, then, at my leisure, I had branded her and locked on her fair throat the gleaming, inflexible circlet of bondage. Before the fall of darkness, and my escape, I had had time, too, to pierce her ears, that the full degree of her degradation and slavery, in the Gorean way of thinking, be made most clear.

To Gorean eyes the piercing of the ears, this visible set of wounds, inflicted to facilitate the mounting of sensual and barbaric ornamentations, is customarily regarded as being tantamount, for most practical purposes, to a sentence of irrevocable bondage. Normally ear-piercing is done only to the lowest and most sensuous of slaves. It is regarded, by most Goreans, as being far more humiliating and degrading to a woman than the piercing of a girl's septum and the consequent fastening on her of a nose ring. Indeed, such an aperture does not even show. Some slave girls, of course, are fixed for both. Their masters, thus, have the option of ornamenting their lovely properties as they please. It might be mentioned that nose rings are favored in some areas more than in others, and by some peoples more than others. On behalf of the nose ring, too, it should be mentioned that among the Wagon Peoples, even free women wear such rings. This, however, is unusual on Gor. The nose ring, most often, is worn by a slave.

These rings, incidentally, those for the ears and for the nose, do not serve simply to bedeck the female. They also have a role to play in her arousal. The brushing of the sides of the girl's neck by the dangling ornament is, in itself, a delicate stimulation of a sensitive area of her body, the sides of her neck beneath the ears; this area is quite sensitive to light touches; if the earring is of more than one piece, the tiny sounds made by it, too, can also be stimulatory; accordingly, the earring's feel and movement, and caress, and sometimes sound, persistent, subtle and sensual, functioning on both a conscious and subliminal level, can often bring a female to, and often keep her indefinitely in, a state of incipient sexual readiness. It is easy to see why free women on Gor do not wear them, and why they are, commonly, only put on low slaves. Similar remarks hold, too, of course, for the nose ring, which touches, lightly, the very sensitive area of a girl's upper lip. The nose ring, too, of course, makes clear to the girl that she is a domestic animal. Many domestic animals on Gor wear them.

The girl kneeling before me, once Elicia Nevins, once the lofty, beautiful and proud agent of Kurii, now only my lovely slave, reached for my sandals. She pressed them to her lips, kissing them, and then, head down, began to tie them on my feet. She was quite beautiful, kneeling before me, performing this lowly task, the heavy iron collar and chain on her neck.

I wondered what the emissary of Samos might wish.

"Your sandals are tied, Master," said the girl, lifting her head, kneeling back.

I regarded her. It is pleasant to own a woman.

"Of what are you thinking, Master?" she asked.

"I was thinking," I said, "of the first time that I put you to my pleasure. Do you recall it?"

"Yes, Master," she said. "I have never forgotten. And it was not only the first time that you put me to your pleasure. It was the first time that any man had put me to his pleasure."

"As I recall," I said, "you yielded well, for a new slave."

"Thank you, Master," she said. "And while you were waiting for darkness, to escape the city, whiling away the time, you made me yield again and again."

"Yes," I said. I had then, after the fall of darkness, deeming it then reasonably safe, bound her naked, belly up, over the saddle of my tarn and, eluding patrols, escaped from the city. I had brought her back to Port Kar, where I had thrown her, a bound slave, to the feet of Samos. He had had her put in one of his girl dungeons, where we had interrogated her. We had learned much. After she had been emptied of information she might then be bound naked and thrown to the urts in the canals, or, perhaps, if we wished, kept as a slave. She was comely. I had had her hooded and brought to my house. When she was unhooded she found herself at my feet.

"Are you grateful that you were spared?" I asked.

"Yes, Master," she said, "and particularly that you have seen fit to keep me, if only for a time, as your own slave."

Nothing so fulfills a woman as her own slavery.

After I had used her, I had put her with my other women. Most of these are available to my men, as well as to myself.

"A girl is grateful," she said, "that this night you had her chained to your slave ring."

"Who is grateful?" I asked.

"Elicia is grateful," she said.

"Who is Elicia?" I asked.

"I am Elicia," she said. "That is the name my Master has seen fit to give me."

I smiled. Slaves, no more than other animals, do not have names in their own right. They are named by the master. She wore her former name, but now only as a slave name, and by my decision.

I stood up, and drew about me one of the furs from the couch. I went to the side of the room and, with a belt, belted the fur about me. Also, from the wall, from its peg, I took down the scabbard with its sheathed short sword. I removed the blade from the scabbard and wiped it on the fur I had belted about me. I then reinserted the blade in the scabbard. The blade is wiped to remove moisture from it. Most Gorean scabbards are not moisture proof, as this would entail either too close a fit for the blade or an impeding flap. I slung the scabbard strap over my left shoulder, in the Gorean fashion. In this way the scabbard, the blade once drawn, may be discarded, with its strap, which accouterments, otherwise, might constitute an encumbrance in combat. On marches, incidentally, and in certain other contexts, the strap, which is adjustable, is usually put over the right shoulder. This minimizes slippage in common and recurrent motion. In both cases, of course, for a right-handed individual, the scabbard is at the left hip, facilitating the convenient and swift across-the-body draw.

I then went again to the side of the fur-strewn, great stone couch, at the side of which, on the tiles, chained by the neck, knelt the beautiful slave.

I stood before her.

She lowered herself to her belly and, holding my ankles gently with her hands, covered my feet with kisses. Her lips, and her tongue, were warm and wet.

"I love you, my Master," she said, "and I am yours."

I stepped back from her. "Go to the foot of the couch," I told her, "and curl there."

"Yes, Master," she said. She then, on her hands and knees, crawled to the foot of the couch and, drawing up her legs, curled there on the cold tiles.

When I went to the door, I stopped and looked back, once, at her. She, curled there on the cold, damp tiles, at the foot of the couch, the chain on her neck, regarded me.

The only light in the room was from the tiny tharlarion-oil lamp which, earlier, Thurnock had placed on the shelf near the door.

"I love you, my Master," she said, "and I am yours."

I then turned about and left the room. In a few Ahn, near dawn, men would come to the room and free her, and then, later, put her to work with the other women.

* * * *

"How many are there?" I asked Samos.

"Two," he said.

"Are they alive?" I asked.

"Yes," he said.

"This seems an unpropitious place for a meeting," I said. We were in the remains of a half-fallen, ruined tarn complex, built on a wide platform, at the edge of the rence marshes, some four pasangs from the northeast delta gate of Port Kar. In climbing to the platform, and in traversing it, the guards with us, who had now remained outside, had, with the butts of their spears, prodded more than one sinuous tharlarion from the boards, the creature then plunging angrily, hissing, into the marsh. The complex consisted of a tarn cot, now muchly open to the sky, with an anterior building to house supplies and tarn keepers. It had been abandoned for years. We were now within the anterior building. Through the ruined roof, between unshielded beams, I could see patches of the night sky of Gor, and one of her three moons. Ahead, where a wall had mostly fallen, I could see the remains of the large tarn cot. At one time it had been a huge, convex, cagelike lacing of mighty branches, lashed together, a high dome of fastened, interwoven wood, but now, after years of disrepair, and the pelting of rains and the tearings of winds, little remained of this once impressive and intricate structure but the skeletal, arched remnants of its lower portions.

"I do not care for this place," I said.

"It suits them," said Samos.

"It is too dark," I said, "and the opportunities for surprise and ambush are too abundant."

"It suits them," said Samos.

"Doubtless," I said.

"I think we are in little danger," he said. "Too, guards are about."

"Could we not have met in your holding?" I asked.

"Surely you could not expect such things to move easily about among men?" asked Samos.

"No," I granted him.

"I wonder if they know we are here," said Samos.

"If they are alive," I said, "they will know."

"Perhaps," said Samos.

"What is the purpose of this parley?" I asked.

"I do not know," said Samos.

"Surely it is unusual for such things to confer with men," I said.

"True," granted Samos. He looked about himself, at the dilapidated, ramshackle building. He, too, did not care overly much for his surroundings.

"What can they want?" I wondered.

"I do not know," said Samos.

"They must, for some reason, want the help of men," I speculated.

"That seems incredible," said Samos.

"True," I said.

"Could it be," asked Samos, "that they have come to sue for peace?"

"No," I said.

"How can you know that?" asked Samos.

"They are too much like men," I said.

"I shall light the lantern," said Samos. He crouched down and extracted a tiny fire-maker from his pouch, a small device containing a tiny reservoir of tharlarion oil, with a tharlarion-oil-impregnated wick, to be ignited by a spark, this generated from the contact of a small, ratcheted steel wheel, spun by a looped thumb handle, with a flint splinter.

"Need this meeting have been so secret?" I asked.

"Yes," said Samos.

We had come to this place, through the northeast delta gate, in a squarish, enclosed barge. It was only through slatted windows that I had been able to follow our passage. Any outside the barge, on the walkways along the canals, for example, could not have viewed its occupants. Such barges, though with the slats locked shut, are sometimes used in the transportation of female slaves, that they may not know where in the city they are, or where they are being taken. A similar result is obtained, usually, more simply, in an open boat, the girls being hooded and bound hand and foot, and then being thrown between the feet of the rowers.

I heard the tiny wheel scratch at the flint. I did not take my eyes from the things at the far end of the room, on the floor, half hidden by a large table, the area open behind them leading to the ruined tarn cot. It is not wise to look away from such things, if they are in the vicinity, or to turn one's back upon them. I did not know if they were asleep or not. I guessed that they were not. My hand rested on the hilt of my sword. Such things, I had reason to know, could move with surprising speed.

The wick of the fire-maker was now aflame. Samos, carefully, held the tiny flame to the wick of the now-unshuttered dark lantern. It, too, burned tharlarion oil.

I was confident now, in the additional light, that the things were not asleep. When the light had been struck, with the tiny noise, from the steel and flint, which would have been quite obvious to them, given the unusual degree of their auditory acuity, there had been only the slightest of muscular contractions. Had they been startled out of sleep, the reaction, I was confident, would have been far more noticeable. I had little doubt they were, and had been, from the first, clearly and exactly aware of our presence.

"The fewer who know of the warrings of worlds, the better," said Samos. "Little is to be served by alarming an unready populace. Even the guards outside do not understand, clearly, on what business we have come here. Besides, if one had not seen such things, who would believe stories as to their existence? They would be regarded as mythical or as existing only in stories of wondrous animals, such as the horse, the dog and griffin."

I smiled. Horses and dogs did not exist on Gor. Goreans, on the whole, knew them only from legends, which, I had little doubt, owed their origins to forgotten times, to memories brought long ago to Gor from another world. Such stories, for they were very old on Gor, probably go back thousands of years, dating from the times of very early Voyages of Acquisition, undertaken by venturesome, inquisitive creatures of an alien species, one known to most Goreans only as the Priest-Kings. To be sure, few Priest-Kings, now, entertained such a curiosity nor such an enthusiastic penchant for exploration and adventure. Now, the Priest-Kings, I feared, had become old. I think that perhaps one is old only when one has lost the desire to know. Not until one has lost one's curiosity, and concern, can one be said to be truly old.

I had two friends, in particular, who were Priest-Kings, Misk, and Kusk. I did not think that they, in this sense, could ever grow old. But they were only two, two of a handful of survivors of a once mighty race, that of the lofty and golden Priest-Kings. To be sure, I had managed, long ago, to return the last female egg of Priest-Kings to the Nest. Too, among the survivors, protected from assassination by the preceding generation, there had been a young male. But I had never learned what had occurred in the Nest after the return of the egg. I did not know if it had been viable, or if the male had been suitable. I did not know if it had hatched or not. I did not know if, in the Nest, a new Mother now reigned or not. If this were the case I did not know the fate of the older generation, nor the nature of the new. Would the new generation be as aware of the dangers in which it stood as had been the last? Would the new generation understand, as well as had the last, the kind of things that, gigantic, shaggy and dark, intertwined, lay a few feet before me now? "I think you are right, Samos," I said.

He lifted the lantern now, its shutters open.

We viewed the things before us.

"They will move slowly," I said, "that they may not startle us. I think that we, too, should do the same."

"Agreed," said Samos.

"There are tarns in the tarn cot," I said. I had just seen one move, and the glint of moonlight off a long, scimitarlike beak. I then saw it lift its wings, opening and shutting them twice. I had not detected them earlier in the shadows.

"Two," said Samos. "They are their mounts."

"Shall we approach the table?" I asked.

"Yes," said Samos.

"Slowly," I said.

"Yes," said Samos.

We then, very slowly, approached the table. Then we stood before it. I could see now, in the light of the lantern, that the fur of one of the creatures was a darkish brown, and the fur of the other was almost black. The most common color in such things is dark brown. They were large. As they lay, together, the crest of that heap, that living mound, marked by the backbone of one of them, was a few inches higher than the surface of the table. I could not see the heads. The feet and hands, too, were hidden. I could not, if I had wished, because of the table, have easily drawn the blade and struck at them. I suspected that the position they had taken was not an accident. Too, of course, from my point of view, I was not displeased to have the heavy table where it was. I would not have minded, in fact, had it been even wider. One tends to be most comfortable with such things, generally, when they are in close chains, with inch-thick links, or behind close-set bars, some three inches in diameter.

Samos set the lantern down on the table. We then stood there, not moving.

"What is to be done?" asked Samos.

"I do not know," I said. I was sweating. I could sense my heart beating. My right hand, across my body, was on the hilt of my sword. My left hand steadied the sheath.

"Perhaps they are sleeping," whispered Samos.

"No," I said.

"They do not signal their recognition of our presence," said Samos.

"They are aware we are here," I said.

"What shall we do?" asked Samos. "Shall I touch one?"

"Do not," I whispered, tensely. "An unexpected touch can trigger the attack reflex."

Samos drew back his hand.

"Too," I said, "such things are proud, vain creatures. They seldom welcome the touch of a human. The enraged and bloody dismemberment of the offender often follows upon even an inadvertent slight in this particular."

"Pleasant fellows," said Samos.

"They, too," I said, "like all rational creatures, have their sense of propriety and etiquette."

"How can you regard them as rational?" asked Samos.

"Obviously their intelligence, and their cunning, qualifies them as rational," I said. "It might interest you to know that, from their point of view, they commonly regard humans as subrational, as an inferior species, and, indeed, one they commonly think of in terms little other than of food."

"Why, then," asked Samos, "would they wish this parley?"

"I do not know," I said. "That is, to me, a very fascinating aspect of this morning's dark business."

"They do not greet us," said Samos, irritably. He was, after all, an agent of Priest-Kings, and, indeed, the first captain of the council of captains, that body sovereign in the affairs of Port Kar.

"No," I said.

"What shall we do?" he asked.

"Wait," I suggested.

We heard, outside, the screaming of a predatory ul, a gigantic, toothed, winged lizard, soaring over the marshes.

"How was this rendezvous arranged?" I asked.

"The original contact was made by a pointed, weighted message cylinder, found upright two days ago in the dirt of my men's exercise yard," said Samos. "Doubtless it was dropped there at night, by someone on tarnback."

"By one of them?" I asked.

"That seems unlikely," said Samos, "over the city."

"Yes," I said.

"They have their human confederates," he said.

"Yes," I said. I had, in my adventures on Gor, met several of the confederates of such creatures, both male and female. The females, invariably, had been quite beautiful. I had little doubt that they had been selected, ultimately, with the collar in mind, that they might, when they had served their purposes, be reduced to bondage. Doubtless this projected aspect of their utility was not made clear to them in their recruitment. She who had once been Miss Elicia Nevins, now the slave Elicia in my holding, chained now nude by the neck to my slave ring, had been such a girl. Now, however, instead of finding herself the slave of one of her allies, or being simply disposed of in a slave market, she found herself the slave of one of her former enemies. That, I thought, particularly on Gor, would give her slavery a peculiarly intimate and terrifying flavor. It was an Ahn or so until dawn now. Soon, doubtless, she would be released from the ring. She would be supervised in relieving and washing herself. Then she would be put with my other women. She then, like the others, after having been issued her slave gruel, and after having finished it, and washed the wooden bowl, would be assigned her chores for the day.

We heard, again, the screaming of the ul outside the building. The tarns in the tarn cot moved about. The ul will not attack a tarn. The tarn could tear it to pieces.

"We have been foolish," I said to Samos.

"How so?" asked Samos.

"Surely the protocols in such a matter, from the point of view of our friends, must be reasonably clear."

"I do not understand," said Samos.

"Put yourself in their place," I said. "They are larger and stronger than we, and quite possibly more ferocious and vicious. Too, they regard themselves as more intelligent than ourselves, and as being a dominant species."

"So?" asked Samos.

"So," said I, "naturally they expect not to address us first, but to be first addressed."

"I," asked Samos, "first speak to such as they, I, who am first captain in the high city of Port Kar, jewel of gleaming Thassa?"

"Correct," I said.

"Never," said he.

"Do you wish me to do so?" I asked.

"No," said Samos.

"Then speak first," I said.

"We shall withdraw," said Samos, angrily.

"If I were you," I said, "I do not think I would risk displeasing them."

"Do you think they would be angry?" he asked.

"I expect so," I said. "I do not imagine they would care to have been fruitlessly inconvenienced by human beings."

"Perhaps I should speak first," said Samos.

"I would recommend it," I said.

"They it is, after all," said he, "who have called this meeting."

"True," I encouraged him. "Also, it would be deplorable, would it not, to be torn to pieces without even having discovered what was on their minds?"

"Doubtless," said Samos, grimly.

"I can be persuasive," I admitted.

"Yes," agreed Samos.

Samos cleared his throat. He was not much pleased to speak first, but he would do it. Like many slavers and pirates, Samos was, basically, a good fellow.

"Tal," said Samos, clearly, obviously addressing this greeting to our shaggy confreres. "Tal, large friends."

We saw the fur move, gigantic muscles slowly, evenly, beginning to stir beneath it. As they had lain it would have been difficult to detect, or strike, a vital area. Sinuously, slowly, the two creatures separated and then, slowly, seemed to rise and grow before us. Samos and I stepped back. Their heads and arms were now visible. The light reflected back, suddenly, eccentrically, from the two large eyes of one of them. For an instant they blazed, like red-hot copper disks, like those of a wolf or coyote at the perimeter of a firelit camp.

I could now, the angle of the lighting being different, see them, blinking, as the large, deep orbs they were. I could see the pupils contracting. Such creatures are primarily nocturnal. Their night vision is far superior to that of the human. Their accommodation to shifting light conditions is also much more rapid than is that of the human. These things have been selected for in their bloody species. When the eyes of the creature had reflected back the light, the light, too, had suddenly reflected back from its fangs, and I had seen, too, the long, dark tongue move about on the lips, and then draw back into the mouth.

The creatures seemed to continue to grow before us. Then they stood erect before us. Their hind legs, some eight to ten inches in width, are proportionately shorter than their arms, which tend to be some eight inches in width at the biceps and some five inches, or so, in width at the wrist. Standing as they were, upright, the larger of the two creatures was some nine feet tall, and the smaller some eight and a half feet tall. I conjecture the larger weighed about nine hundred pounds and the smaller about eight hundred and fifty pounds. These are approximately average heights and weights for this type of creature. Their hands and feet are six digited, tentaclelike and multiply jointed. The nails, or claws, on the hands, are usually filed, presumably to facilitate the manipulation of tools and instrumentation. The claws, retractable, on the feet are commonly left unfiled. A common killing method for the creature is to seize the victim about the head or shoulders, usually with the teeth, and, raking, to disembowel it with the tearing of the clawed hind feet. Other common methods are to hold the victim and tear away the throat from between the head and body, or to bite away the head itself.

"Tal," repeated Samos, uneasily.

I looked across the table at the creatures. I saw intelligence in their eyes.

"Tal," repeated Samos.

Their heads were better than a foot in width. Their snouts were two-nostriled, flattish and leathery. Their ears were large, wide and pointed. They were now erected and oriented towards us. This pleased me, as it indicated they had no immediate intention of attacking. When such a creature attacks the ears flatten against the sides of the head, this having the apparent function of reducing their susceptibility to injury. This is a common feature of predatory carnivores.

"They do not respond," said Samos.

I did not take my eyes from the creatures. I shrugged. "Let us wait," I said. I was uncertain as to what alien protocols the creatures might expect us to observe.

The creatures stood upright now but they could function as well on all fours, using the hind legs and the knuckles of the hands. The upright carriage increases scanning range, and has probably contributed to the development and refinement of binocular vision. The horizontal carriage permits great speed, and has probably contributed, via natural selections, to the development of olfactory and auditory acuity. In running, such creatures almost invariably, like the baboon, have recourse to all fours. They will normally drop to all fours in charging, as well, the increased speed increasing the impact of their strike.

"One is a Blood," I said.

"What is that?" asked Samos.

"In their military organizations," I said, "six such beasts constitute a Hand, and its leader is called an Eye. Two hands and two eyes constitute a larger unit, called a "Kur" or "Beast," which is commanded by a leader, or Blood. Twelve such units constitute a Band, commanded again by a Blood, though of higher rank. Twelve bands, again commanded by a Blood, of yet higher rank, constitute a March. Twelve Marches is said to constitute a People. These divisors and multiples have to do with, it seems, a base-twelve mathematics, itself perhaps indexed historically to the six digits of one of the creature's prehensile appendages."

"Why is the leader spoken of as a Blood?" asked Samos.

"It seems to have been an ancient belief among such creatures," I said, "that thought was a function of the blood, rather than of the brain, a terminology which has apparently lingered in their common speech. Similar anachronisms occur in many languages, including Gorean."

"Who commands a People?" asked Samos.

"One who is said to be a 'Blood' of the People, as I understand it," I said.

"How do you know that one of these is a 'Blood,'" asked Samos.

"The left wrist of the larger animal bears two rings, rings of reddish alloy," I said. "They are welded on the wrist. No Gorean file can cut them."

"He is then of high rank?" asked Samos.

"Of lower rank than if he wore one," I said. "Two such rings designate the leader of a Band. He would have a ranking, thusly, of the sort normally accorded to one who commanded one hundred and eighty of his fellows."

"He is analogous to a captain," said Samos.

"Yes," I said.

"But not a high captain," said Samos.

"No," I said.

"If he is a Blood, then he is almost certainly of the steel ships," said Samos.

"Yes," I said.

"The other," said Samos, "wears two golden rings in its ears."

"It is a vain beast," I said. "Such rings serve only as ornaments. It is possible he is a diplomat."

"The larger beast seems clearly dominant," said Samos.

"It is a Blood," I said.

There was a broad leather strap, too, running from the right shoulder to the left hip of the smaller of the two creatures. I could not see what accouterment it bore.

"We have greeted them," said Samos. "Why do they not speak?"

"Obviously we must not yet have greeted them properly," I said.

"How long do you think they will remain tolerant of our ignorance?" asked Samos.

"I do not know," I said. "Such creatures are not noted for their patience."

"Do you think they will try to kill us?" asked Samos.

"They have already had ample opportunity to attempt to do so, if that were their intention," I said.

"I do not know what to do," said Samos.

"The occasion is formal, and we are dealing with a Blood," I said, "one doubtless from the steel ships themselves. I think I have it."

"What do you recommend?" asked Samos.

"How many times have you proffered greetings to them?" I asked.

Samos thought, briefly. "Four," he said. "'Tal' was said to them four times."

"Yes," I said. "Now, if one of these beasts were to touch the hand, or paw, of another, the hand, or paw, of each being open, indicating that weapons were not held, that the touch was in peace, at how many points would contact be made?"

"At six," said Samos.

"Such creatures do not care, usually, to be touched by humans," I said. "The human analogy to such a greeting then might be six similar vocal signals. At any rate, be that as it may, I think the number six is of importance in this matter."

Samos then held up his left hand. Slowly, not speaking, he pointed in succession to four fingers. He then held the small finger of his left hand in his right hand. "Tal," he said. Then he held up the index finger of his right hand. "Tal," he said again.

Then, slowly, the smaller of the two creatures began to move. I felt goose pimples. The hair on the back of my neck stood up.

It turned about and bent down, and picked up a large shield, of a sort adequate for such a creature. It lifted this before us, displaying it, horizontally, convex side down. We could see that the shield straps were in order. It then placed the shield on the floor, to the side of the table, to their left. It then went back and again bent down. This time it brought forth a mighty spear, some twelve feet in length, with a long, tapering bronze head. This, with two hands, holding it horizontally, across its body, it also displayed, lifting it ceremoniously upwards and towards us, and then drawing it back. It then put the spear down, laying it on the floor, to their left. The shaft of the spear was some three inches in diameter. The bronze head might have weighed some twenty pounds.

"They honor us," said Samos.

"As we did them," I said.

The symbolism of the creature's action, the lifting of weapons, and then the setting aside of them, was clear. This action also, of course, was in accord with the common Gorean convention in proposing a truce. That the creatures had seen fit to utilize this convention, one of humans, was clear. I found this a welcome accommodation on their part. They seemed concerned to be congenial. I wondered what they wanted. To be sure, however, it was only the lighter colored, and smaller, of the two creatures, that with rings in its ears, which had performed these actions. It might, indeed, be, for most practical purposes, a diplomat. The larger creature, the Blood, had stood by, unmoving. Yet clearly these actions had been performed in its presence. This, then, was sufficient evidence of their acceptance on its part. I noted, the sort of thing a warrior notes, that the spear had been placed to their left, and that its head, too, was oriented to their left. It was thus placed, and oriented, in such a way that the Blood, which stood on the left, from their point of view, if it favored the right hand, or paw, as most such creatures do, rather like humans, could easily bend down and seize it up.

"I see they have not come to surrender," said Samos.

"No," I said. The shield straps, which had been displayed to us with the shield, the shield held convex side down, had not been torn away or cut, which would have rendered the shield useless. Similarly the shaft of the spear had not been broken. They had not come to surrender.

The lips of the smaller of the two creatures drew back, exposing the fangs. Samos stepped back. His hand went to the hilt of his sword.

"No," I said to him, quietly. "It is trying to imitate a human smile."

The creature then detached, from the broad strap which hung diagonally about its body, from its right shoulder to the left hip, an instrumented, metallic, oblong, boxlike device, which it placed on the table.

"It is a translator," I said to Samos. I had seen one in a complex, some years earlier, in the north.

"I do not trust such creatures," said Samos.

"Some of them, specially trained," I said, "can understand Gorean."

"Oh," said Samos.

The smaller of the two creatures turned to the larger. It said something to him. The speech of such creatures resembles a succession of snarls, growls, rasps and throaty vibrations. The noises emitted are clearly animal noises, and, indeed, such as might naturally be associated with a large and powerful, predatory carnivore; yet, on the other hand, there is a liquidity, and a precision and subtlety about them which is unmistakable; one realizes, often uneasily, that what one is listening to is a language.

The larger one inclined its huge, shaggy head, and then lifted it. The tips of two long, curved fangs, in the position of the upper canines, protruded slightly from its closed mouth. It watched us.

The smaller of the two creatures then busied itself with the device on the table.

Lowering the head is an almost universal assent gesture, indicating submission to, or agreement with, the other. The dissent gesture, on the other hand, shows much greater variety. Shaking the head sideways, among rational creatures, may be taken as a negation of assent. Other forms of the nonassent gesture can be turning the head away from the other, sometimes with a gesture of the lips, indicating distaste, or even of ejecting an unwanted substance from the mouth, backing away, or lifting the head and extending the neck, sometimes baring the fangs and tensing the body, as in a variation on the bristling response.

"To be sure," I said, "it is extremely difficult for them to speak Gorean, or another human language." It was difficult for them, of course, given the nature of their oral cavity, throat, tongue, lips and teeth, to produce human phonemes. They can, however, sometimes in a horrifying way, approximate them. I shuddered. I had, once or twice, heard such creatures speaking Gorean. It had been disconcerting to hear human speech, or something resembling human speech, emanating from such a source. I was just as pleased that we had a translator at our disposal.

"Look," said Samos.

"I see," I said.

A small, conical, red light began to glow on the top of the machine.

The slighter of the two monsters then drew itself up. It began to speak.

We understood, initially, of course, nothing of what it said. We listened to it, not moving, in the dim, pale-yellowish, flickering light of the unshuttered dark lantern, amidst the dark, dancing shadows in that abandoned tarn complex.

I remember noting the glinting of the golden rings in its ears, and the moistness of saliva about its dark lips and on its fangs.

"I am Kog," came from the translator. "I am below the rings. With me is Sardak, who is within the rings. I speak on behalf of the Peoples, and the chieftains of the Peoples, those who stand above the rings. I bring you greetings from the Dominants, and from the Conceivers and Carriers. No greetings do I bring you from those unworthy of the rings, from the discounted ones, the unnamed and craven ones. Similarly no greetings do I bring you from our domestic animals, those who are human and otherwise. In short, honor do I do unto you, bringing you greetings from those who are entitled to extend greetings, and bringing you no greetings from those unworthy to give greetings. Thus, then, do I bring you greetings on behalf of the Peoples, on behalf of the ships, and the Steel Worlds. Thus, then, do I bring you greetings on behalf of the cliffs of the thousand tribes." These words, and word groups, came forth from the translator, following intervals between the creature's inputs. They are produced in a flat, mechanical fashion. The intonation contours, as well as meaningful tonal qualities, pitches and stresses, from which one can gather so much in living speech, unfortunately, tend to be absent or only randomly correlated in such a formal, desiccated output. Similarly the translation, it seems, is often imperfect, or, at least, awkward and choppy. Indeed, it takes a few moments before one can begin to follow the productions of such a machine coherently but, once this adjustment is made, there is little difficulty in comprehending the gist of what is being conveyed. In my presentation of the machine's output I have, here and there, taken certain liberties. In particular I have liberalized certain phrasings and smoothed out various grammatical irregularities. On the other hand, given the fact that I am conveying this material in English, at two removes from the original, I think that the above translation, and what follows, is not only reasonably adequate in a literal sense, but also conveys something, at least, of the flavor of the original. On the other hand, I do not claim to understand all aspects of the translation. For example, I am unclear on the ring structure and on the significance of the references to tribal cliffs.

"I think, Samos," I said, "you are expected to respond."

"I am Samos," said Samos, "and I thank you for your cordial and welcome salutations."

Fascinated, Samos and I listened to what was, with one exception, a succession of rumbling, throaty utterances emanating from the machine. The machine apparently accepted and registered Gorean phonemes, and then scanned the phonemic input for those phoneme combinations which expressed Gorean cognitive units, or morphemes. In this way, morphemes, per se, or linguistic cognitive units, at least as comprehended units, do not occur in the machine. With a human translator sound is processed, and understood morphemically, which understanding is then reprocessed into the new phonemic structures. With the machine the correlation is simply between sound structures, simpliciter, and it is the auditor who supplies the understanding. To be sure, a linguistic talent of no mean degree is required to design and program such a device. We did hear one Gorean word in the translation. That was the name 'Samos'. When the machine encounters a phoneme or phonemic combination which is not correlated with a phoneme or phoneme combination in the new language it presents the original input as a portion of the new output. For example, if one were to utter nonsense syllables into the device the same nonsense syllables, unless an accident or a coincidence occurred, would be played back.

The creatures, then, heard the name of Samos. Whether they could pronounce it or not, or how close they could come to pronounce it, would depend on the sound and on the capacity of their own vocal apparatus. This is different, it should be noted, with the names of the two creatures, 'Kog' and 'Sardak'. These names were given in Gorean phonemes, not in the phonemes of the creatures' own language. In this case, of course, this made it clear that these two names, at least, had been programmed into the machine. The machine, doubtless, had been altered to be of aid to two particular individuals in some particular mission. Presumably Samos and I could not have pronounced the actual names of the creatures. 'Kog' and 'Sardak', however, doubtless correlated in some fashion, given some type of phonemic transcription found acceptable by the creatures, with their actual names. There was probably, at least, a syllabial correlation.

"I bring you greetings," said Samos, "from the Council of Captains, of Port Kar, Jewel of Gleaming Thassa."

I saw the lips of the two creatures draw back. I, too, smiled. Samos was cautious, indeed. What would the Council of Captains know of such creatures, or of the warrings among worlds? He had not identified himself as being among the party of those forces arrayed against the ravaging, concupiscent imperialism of our savage colleagues. I myself, whereas I had served Priest-Kings, did not regard myself as being of their party. My lance, in such matters, so to speak, was free. I would choose my own wars, my own ventures.

"I bring you greetings, too," said Samos, "from the free men of Port Kar. I do not bring you greetings, of course, from those who are unworthy to greet you, for example, from our slaves, who are nothing, and who labor for us, and whom we use for our sport and pleasure."

Kog briefly inclined his head. I thought Samos had done rather well. Slaves on Gor are domestic animals, of course. A trained sleen in a sleen market will usually bring a higher price than even a beautiful girl sold naked in a slave market. This is doubtless a function of supply and demand. Beautiful female slaves are generally cheap on Gor, largely as a result of captures and breedings. It is not unusual, in most cities, for a prize tarsk to bring a higher price than a girl. The girls understand this, clearly, and it helps them to understand their place in the society.

"I speak on behalf of the Peoples, on behalf of the Steel Worlds," said Kog.

"Do you speak on behalf of all the Peoples, on behalf of all the Steel Worlds?" asked Samos.

"Yes," said Kog.

"Do you speak on behalf of all of those of the Peoples, of all of those of the Steel Worlds?" asked Samos. This, I thought, was an interesting question. It was, of course, subtly different from the preceding question. We knew that divisions as to tactics, if not ultimate objectives, existed among parties of such creatures. We had learned this in the Tahari.

"Yes," said Kog, unhesitantly.

When Kog had made his response to the question I was, by intent, watching not him but the other of the two creatures. Yet I saw no flicker of doubt or uneasiness in his eyes, nor any incipient lifting of the broad ears. It did, however, draw its lips back slightly, observing my attention. It had apparently found my attempt to read its behavioral cues amusing.

"Do you speak on behalf of Priest-Kings?" asked Kog.

"I cannot," said Samos.

"That is interesting," said Kog.

"If you would speak with Priest-Kings," said Samos, "you must go to the Sardar."

"What are Priest-Kings?" asked Kog.

"I do not know," said Samos.

Such creatures, I gathered, had no clear idea of the nature of Priest-Kings. They had not directly experienced Priest-Kings, only the power of Priest-Kings. Like burned animals they were wary of them. Priest-Kings, wisely, did not choose to directly confront such creatures. Not a little of the hesitancy and tentativeness of the militaristic incursions of such creatures was, I suspected, a function of their ignorance of, and fear of, the true nature and power of the remote and mysterious denizens of the Sardar. If such creatures should come to clearly understand the nature of the Priest-Kings, and the current restrictions on their power, in virtue of the catastrophic Nest War, I had little doubt but what the attack signals would be almost immediately transmitted to the steel worlds. In weeks the silver ships would beach on the shores of Gor.

"We know the nature of Priest-Kings," said Kog. "They are much like ourselves."

"I do not know," said Samos.

"They must be," said Kog, "or they could not be a dominant life form."

"Perhaps," said Samos. "I do not know."

The larger of the two creatures, during this exchange, was watching me. I smiled at him. Its ears twitched with annoyance. Then again it was as it had been, regal, savage, distant, unmoving and alert.

"Can you speak on behalf of the men of the two worlds?" asked Kog. This was a reference, doubtless, to the Earth and Gor.

"No," said Samos.

"But you are a man," said Kog.

"I am only one man," said Samos.

"Their race has not yet achieved species unification," said the larger of the two creatures, to his fellow. His remark, of course, was picked up by the translator and processed, as though it had been addressed to us.

"That is true," said Kog. I wondered, hearing this, if the beasts, either, had achieved species unification. I was inclined to doubt it. Such creatures, being territorial, individualistic and aggressive, much like men, would not be likely to find the bland idealisms of more vegetative organisms interesting, attractive or practical. Logical, and terrible, they would not be likely to find the fallacy of the single virtue, the hypothesis of social reductivism, alluring.

All creatures are not the same, nor is it necessary that they should be. Jungles may be as appealing to nature as gardens. Leopards and wolves are as legitimately ingredient in the order of nature as spaniels and potatoes. Species unification, I suspected, would prove not to be a blessing, but a trap and a bane, a pathology and curse, a societal sanitarium in which the great and strong would be reduced to, or must pretend to be reduced to, the level of the blinking, the cringing, the creeping and the tiny. To be sure, values are involved here, and one must make decisions. It is natural that the small and weak will make one decision, and the large and strong another. There is no single humanity, no single shirt, no correct pair of shoes, no uniform, even a gray one, that will fit all men. There are a thousand humanities possible. He who denies this sees only his own horizons. He who disagrees is the denier of difference, and the murderer of better futures.

"It is unfortunate," said Sardak, speaking to Kog, "that they have not achieved species unification. Else, once the Priest-Kings are disposed of, it would be easier to herd them to our cattle pens."

"That is true," said Kog.

What Sardak said seemed to me, too, likely to be true. Highly centralized structures are the most easily undermined and subverted. Cutting one strand of such a web can unravel a world. One hundred and eighty-three men once conquered an empire.

"Can you speak on behalf of the Council of Captains, of Port Kar?" asked Kog.

"Only on matters having to do with Port Kar, and then after a decision of the council, taken after consultation," said Samos. This was not exactly correct, but it was substantially correct. It seemed to me a suitable answer, under the circumstances. The creatures, of course, would not be familiar with council procedures.

"You do, however, have certain executive powers, do you not?" inquired Kog. I admired the creatures. Clearly they had researched their mission.

"Yes," said Samos, guardedly, "but they are not likely to be involved in matters of the sort with which we are here likely to be concerned."

"I understand," said Kog. "On behalf of whom, then, do you speak?"

"I speak," said Samos, rather boldly I thought, "on behalf of Samos, of Port Kar, on behalf of myself."

Kog snapped off the translator and turned to Sardak. They conversed for a moment in their own tongue. Kog then snapped the translator back on. This time, almost instantly, the small, conical red light began to glow.

"It is sufficient," said Kog.

Samos stepped back a bit.

Kog turned away, then, to a leather tube and, with his large, furred, tentaclelike digits, with their blunted claws, removed the cap from this tube.

I suspected that the two creatures did not believe Samos when he protested to them that he could speak only on behalf of himself. At the least they would be certain that he would be significantly involved in the affairs of Priest-Kings. They would seem to have little alternative, then, to dealing with him.

From the long, leather tube, Kog removed what appeared to be a large piece of closely rolled, soft-tanned hide. It was very light in color, almost white, and tied with string. There was a slight smell of smoke about it, probably from the smoke of the turl bush. Such hides may be waterproofed by suspending them from, and wrapping them about, a small tripod of sticks, this set over a small fire on which, to produce the desiderated smoke, the leaves and branches of the turl bush are heavily strewn.

Kog placed the roll of hide on the table. It was not rawhide, but soft-tanned hide, as I have suggested. In preparing rawhide the skin, suitably fleshed, is pegged down and dried in the wind and sun. The hide may then, without further ado, be worked and cut. This product, crude and tough, may be used for such things as shields, cases and ropes. Soft tanning a hide, on the other hand, is a much more arduous task. In soft tanning, the fleshed hide must be saturated with fats, and with oils and grease, usually from the brains of animals. These are rubbed into the hide, and worked into it, usually with a soft flat stone. The hide is then sprinkled with warm water and tightly rolled, after which it is put aside, away from the sun and heat, for a few days. This gives the time necessary for the softening ingredients, such as the fats and oils, to fully penetrate the leather. The skin is then unrolled and by rubbing, kneading and stretching, hand-softened over a period of hours. The resulting product ranges from tan to creamy white, and may be worked and cut as easily as cloth.

"You are familiar, are you not," asked Kog, "with one known as Zarendargar?"

"Who is Zarendargar?" asked Samos.

"Let us not waste one another's time," said Kog.

Samos turned white.

I was pleased that, outside, on the platform of this anterior building of the tarn complex, there were several guards. They were armed with crossbows. The iron bolts of these devices, weighing about a pound apiece, were capable of sinking some four inches into solid wood at a range of some twenty yards. To be sure, by the time the guards might be summoned Samos and I might be half eaten.

Kog looked closely at Samos.

"Zarendargar," said Samos, "is a well-known commander of the steel worlds, a war general. He perished in the destruction of a supply complex in the arctic."

"Zarendargar is alive," said Kog.

I was startled by this pronouncement. This seemed to me impossible. The destruction of the complex had been complete. I had witnessed this from pasangs across the ice in the arctic night. The complex would have been transformed into a radioactive inferno. Even the icy seas about it, in moments, had churned and boiled.

"Zarendargar cannot be alive," I said. It was the first time I had spoken to the beasts. Perhaps I should not have spoken, but I had been in the vicinity of the event in question. I had seen the explosion. I had, even from afar, been half blinded by the light, and, moments later, half staggered by the sound, the blast and heat. The shape, height and awesomeness of that towering, expanding cloud was not something I would ever forget. "Nothing could have lived in that blast," I said, "nor in the seas about it."

Kog looked at me.

"I was there," I said.

"We know," said Kog.

"Zarendargar is dead," I said.

Kog then unrolled the hide on the table. He arranged it so that Samos and I could easily see it. The hair rose up on the back of my neck.

"Are you familiar with this sort of thing?" asked Kog of Samos.

"No," said Samos.

"I have seen things like it," I said, "but only far away, on another world. I have seen things like it in places called museums. Such things are no longer done."

"Does the skin seem to you old," asked Kog, "faded, brittle, cracked, worn, thin, fragile?"

"No," I said.

"Consider the colors," said Kog. "Do they seem old to you? Do they seem faded to you?"

"No," I said. "They are bright, and fresh."

"Analysis, in virtue of desiccation index and molecular disarrangement, suggests that this material, and its applied pigments, are less than two years old. This hypothesis is corroborated by correlation data, in which this skin was compared to samples whose dating is known and independent historical evidence, the nature of which should be readily apparent."

"Yes," I said. I knew that such beasts, on the steel worlds, possessed an advanced technology. I had little doubt but what their physical and chemical techniques were quite adequate to supply the dating in question to the skin and its paints. Too, of course, the nature of their historical evidence would be quite clear. To be sure, it would be historical data at their disposal, and not mine. I had no way of knowing the pertinent facts. That such beasts, on this world, carried primitive weapons was a tribute to their fear of Priest-Kings. Carrying such weapons they might be mistaken for beasts of their race who now, for all practical purposes, were native to Gor, beasts descended from individuals perhaps long ago marooned or stranded on the planet. Priest-Kings, on the whole, tend to ignore such beasts. They are permitted to live as they will, where they may, on Gor, following even their ancient laws and customs, providing these do not violate the Weapons Laws and Technology Restrictions. To be sure, such beasts usually, once separated from the discipline of the ships, in a generation or two, lapsed into barbarism. On the whole they tended to occupy portions of Gor not inhabited by human beings. The Priest-Kings care for their world, but their primary interest is in its subsurface, not its surface. For most practical purposes life goes on on Gor much as though they did not exist. To be sure, they are concerned to maintain the natural ecosystems of the planet. They are wise, but even they hesitate to tamper with precise and subtle systems which have taken over four billion years to develop. Who knows what course a dislodged molecule may take in a thousand years?

I looked at Kog and Sardak. Such creatures, perhaps thousands of years ago, had, it seemed, destroyed their own world. They now wanted another. The Priest-Kings, lofty and golden, remote, inoffensive and tolerant, were all, for most practical purposes, that stood between the Kogs and Sardaks, and the Earth and Gor.

"This is," said Kog, to Samos, "a story skin."

"I understand," said Samos.

"It is an artifact of the red savages," said Kog, "from one of the tribes in the Barrens."

"Yes," said Samos.

The Red Savages, as they are commonly called on Gor, are racially and culturally distinct from the Red Hunters of the north. They tend to be a more slender, longer-limbed people; their daughters menstruate earlier; and their babies are not born with a blue spot at the base of the spine, as is the case with most of the red hunters. Their culture tends to be nomadic, and is based on the herbivorous, lofty kaiila, substantially the same animal as is found in the Tahari, save for the wider footpads of the Tahari beast, suitable for negotiating deep sand, and the lumbering, gregarious, short-tempered, trident-horned kailiauk. To be sure, some tribes do not have the kaiila, never having mastered it, and certain tribes have mastered the tarn, which tribes are the most dangerous of all.

Although there are numerous physical and cultural differences among these people they are usually collectively referred to as the red savages. This is presumably a function of so little being known about them, as a whole, and the cunning, ruthlessness and ferocity of so many of the tribes. They seem to live for hunting and internecine warfare, which seems to serve almost as a sport and a religion for them. Interestingly enough most of these tribes seem to be united only by a hatred of whites, which hatred, invariably, in a time of emergency or crisis, takes precedence over all customary conflicts and rivalries. To attack whites, intruding into their lands, once the war lance has been lifted, even long-term blood enemies will ride side by side. The gathering of tribes, friends and foes alike, for such a battle is said to be a splendid sight. These things are in virtue of what, among these peoples, is called the Memory.

"The story begins here," said Kog, indicating the center of the skin. From this point there was initiated, in a slow spiral, to be followed by turning the skin, a series of drawings and pictographs. As the skin is turned each marking on it is at the center of attention, first, of course, of the artist, and, later, as he follows the trail, of the viewer. The story, then, unanticipated, each event as real as any other, unfolds as it was lived.

"In many respects," said Kog, "this story is not untypical. These signs indicate a tribal camp. Because of the small number of lodges, this is a winter camp. We can also tell this from these dots, which represent snow."

I looked at the drawings. They were exactly, and colorfully done. They were, on the whole, small, and precise and delicate, like miniatures. The man who had applied the pigments to that hide canvas had been both patient and skillful. Too, he had been very careful. This care is often a feature of such works. To speak the truth is very important to the red savages.

"This jagged line," said Kog, "indicates that there is hunger in the camp, the sawing feeling in the stomach. This man, whom we take to be the artist, and whom we shall call Two Feathers, because of the two feathers drawn near him, puts on snowshoes and leaves the camp. He takes with him a bow and arrows."

I watched Kog slowly turn the skin. The drawings are first traced on the skin with a sharp stick. Many of them are then outlined in black. The interior areas, thusly blocked out, may then be colored in. The primary pigments used were yellows, reds, browns and blacks. These are primarily obtained from powdered earths, clays and boiled roots. Blues can be obtained from blue mud, gant droppings and boiled rotten wood. Greens can be obtained from a variety of sources, including earths, boiled rotten wood, copper ores and pond algae. The pigments, commonly mixed with hot water or glue, are usually applied by a chewed stick or a small brush, or pen, of porous bone, usually cut from the edge of the kailiauk's shoulder blade or the end of its hip bone. Both of these bones contain honeycombed structures useful in the smooth application of paint.

"This man travels for two days," said Kog, pointing to two yellow suns in the sky of the hide. "On the third day he finds the track of a kailiauk. He follows this. He drinks melted snow, held in his mouth until it is warm. He eats dried meat. On the third day he builds no fire. We may gather from this he is now in the country of enemies. Toward the evening of the fourth day he sees more tracks. There are other hunters, mounted on kaiila, who, too, are following the kailiauk. It is difficult to determine their number, for they ride single file, that the prints of one beast may obscure and obliterate those of another. His heart is now heavy. Should he turn back? He does not know what to do. He must dream on the matter."

"Surely," said Samos, "it could be only a coincidence."

"I do not think so," said Kog.

"This hide," said Samos, "could be nothing but the product of the crazed imagination of an ignorant savage. It might, too, be nothing more than the account of a strange dream."

"The organization and clarity of the account suggests rationality," said Kog.

"It is only the story of a dream," said Samos.

"Perhaps," said Kog.

"Such people do not distinguish clearly between dreams and reality," said Samos.

"They distinguish clearly between them," said Kog. "It is only that they regard both as real."

"Please, continue," I said.

"Here, in the dream," said Kog, indicating a series of pictographs which followed a small spiral line, "we see that the kailiauk invites the man to a feast. This is presumably a favorable sign. At the feast, however, in the lodge of the kailiauk, there is a dark guest. His lineaments are obscure, as you can see. The man is afraid. He senses great power in this dark guest. The kailiauk, however, tells the man not to be afraid. The man takes meat from the hands of the dark guest. It will be his ally and protector, the kailiauk tells him. He may take it for his medicine. The man awakens. He is very frightened. He is afraid of this strange medicine. The dream is strong, however, and he knows it cannot be repudiated. Henceforth he knows his medicine helper is the mysterious dark guest."

"From where," asked Samos, "does this man think he obtained this medicine helper?"

"Surely the man will think he obtained it from the medicine world," said Kog.

"It seems an interesting anticipatory dream," I said.

"Surely the dream is ambiguous," said Samos. "See? The lineaments of the dark guest are unclear."

"True," I said. "Yet something of its size, and of its awesomeness, and force, particularly within a lodge, seems evident."

"You will also notice," said Kog, "that it sits behind the fire. That is the place of honor."

"It could all be a coincidence," said Samos.

"That is quite true," I said. "Yet the matter is of interest."

"Other explanations, too, are possible," said Samos. "The man may once have seen such things, or heard of them, and forgotten them."

"That seems to me quite likely," I said.

"But why, in the dream, in this dream," asked Samos, "should the dark guest appear?"

"Possibly," I said, "because of the man's plight, and need. In such a situation a powerful helper might be desired. The dream, accordingly, might have produced one."

"Of course," said Samos.

"Considering the events of the next day," said Kog, "I think certain alternative explanations might be more likely. This is not, of course, to rule out that the man, in his quandary, and desperate straits, might not have welcomed a powerful ally."

"What do you suggest?" I asked.

"That he, earlier, during the day, saw sign of the medicine helper, but only in the dream interpreted it."

"I see," I said.

"Even more plausibly, and interestingly," said Kog, "I suspect that the dark guest, in that moonlit snow, actually appeared to the man. The man, hungry, exhausted, striving for the dream, betwixt sleeping and waking, not being fully aware of what was transpiring, saw it. He then incorporated it into his dream, comprehending it within his own conceptual framework."

"That is an interesting idea," I said.

"But it is surely improbable that the paths of the man and the helper should cross in the vast, trackless wastes of the snowbound Barrens," said Samos.

"Not if both were following the kailiauk," said Kog.

"Why would the helper not have eaten the man?" I asked.

"Perhaps," said Kog, "because it was hunting the kailiauk, not the man. Perhaps because if it killed a man, it was apprehensive that other men would follow it, to kill it in turn."

"I see," I said.

"Also," said Kog, "kailiauk is better than man. I know. I have eaten both."

"I see," I said.

"If the helper had visited the man," said Samos, "would there not have been prints in the snow?"

"Doubtless," said Kog.

"Were there prints?" asked Samos.

"No," said Kog.

"Then it was all a dream," said Samos.

"The absence of prints would be taken by the man as evidence that the helper came from the medicine world," said Kog.

"Naturally," said Samos.

"Accordingly the man would not look for them," said Kog.

"It is your hypothesis, however," conjectured Samos, "that such prints existed."

"Of course," said Kog, "which then, in the vicinity of the camp, were dusted away."

"From the point of view of the man, then," said Samos, "the dark guest would have come and gone with all the silence and mystery of a guest from the medicine world."

"Yes," said Kog.

"Interesting," said Samos.

"What is perfectly clear," said Kog, "is how the man viewed the situation, whether he was correct or not. Similarly clear, and undeniably so, are the events of the next day. These are unmistakably and unambiguously delineated." Kog then, with his dexterous, six-jointed, long digits, rotated the skin a quarter of a turn, continuing the story.

"In the morning," said Kog, "the man, inspired by his dream, resumed his hunt. A snow began to fall." I noted the dots between the flat plane of the earth and the semicircle of the sky. "The tracks, with the snow, and the wind, became obscured. Still the man pressed on, knowing the direction of the kailiauk and following the natural geodesics of the land, such as might be followed by a slow-moving beast, pawing under the snow for roots or grass. He did not fear to lose the trail. Because of his dream he was undaunted. On snowshoes, of course, he could move faster through drifted snow than the kailiauk. Indeed, over long distances, in such snow, he could match the speed of the wading kaiila. Too, as you know, the kailiauk seldom moves at night."

The kailiauk in question, incidentally, is the kailiauk of the Barrens. It is a gigantic, dangerous beast, often standing from twenty to twenty-five hands at the shoulder and weighing as much as four thousand pounds. It is almost never hunted on foot except in deep snow, in which it is almost helpless. From kaiilaback, riding beside the stampeded animal, however, the skilled hunter can kill one with a single arrow. He rides close to the animal, not a yard from its side, just outside the hooking range of the trident, to supplement the striking power of his small bow. At this range the arrow can sink in to the feathers. Ideally it strikes into the intestinal cavity behind the last rib, producing large-scale internal hemorrhaging, or closely behind the left shoulder blade, thence piercing the eight-valved heart.

The hunting arrow, incidentally, has a long, tapering point, and this point is firmly fastened to the shaft. This makes it easier to withdraw the arrow from its target. The war arrow, on the other hand, uses an arrowhead whose base is either angled backwards, forming barbs, or cut straight across, the result in both cases being to make the arrow difficult to extract from a wound. The head of the war arrow, too, is fastened less securely to the shaft than is that of the hunting arrow. The point thus, by intent, if the shaft is pulled out, is likely to linger in the wound. Sometimes it is possible to thrust the arrow through the body, break off the point and then withdraw the shaft backwards. At other times, if the point becomes dislodged in the body, it is common to seek it with a bone or greenwood probe, and then, when one has found it, attempt to work it free with a knife. There are cases where men have survived this. Much depends, of course, on the location of the point.

The heads of certain war arrows and hunting arrows differ, too, at least in the case of certain warriors, in an interesting way, with respect to the orientation of the plane of the point to the plane of the nock. In these war arrows, the plane of the point is perpendicular to the plane of the nock. In level shooting, then, the plane of the point is roughly parallel to the ground. In these hunting arrows, on the other hand, the plane of the point is parallel to the plane of the nock. In level shooting, then, the plane of the point is roughly perpendicular to the ground. The reason for these different orientations is particularly telling at close range, before the arrow begins to turn in the air. The ribs of the kailiauk are vertical to the ground; the ribs of the human are horizontal to the ground.

The differing orientations may be done, of course, as much for reasons of felt propriety, or for medicine purposes, as for reasons of improving the efficiency of the missile. They may have some effect, of course, as I have suggested, at extremely close range. In this respect, however, it should be noted that most warriors use the parallel orientation with respect to both their war and hunting points. It is felt that this orientation improves sighting. This seems to me, too, to be the case. The parallel orientation, of course, would be more effective with kailiauk, which are usually shot at extremely close range, indeed, from so close that one might almost reach out and touch the beast. Also, of course, in close combat with humans, if one wishes, the perpendicular alignment may be simply produced; one need only turn the small bow.

"Toward noon," said Kog, slowly turning the hide, "we see that the weather has cleared. The wind has died down. The snow has stopped falling. The sun has emerged from clouds. We may conjecture that the day is bright. A rise in temperature has apparently occurred as well. We see that the man has opened his widely sleeved hunting coat and removed his cap of fur."

"I had not hitherto, before seeing this skin," said Samos, "realized that the savages wore such things."

"They do," said Kog. "The winters in the Barrens are severe, and one does not hunt in a robe."

"Here," said Samos, "the man is lying down."

"He is surmounting a rise," said Kog, "surmounting it with care."

I nodded. It is seldom wise to silhouette oneself against the sky. A movement in such a plane is not difficult to detect. Similarly, before entering a terrain, it is sensible to subject it to some scrutiny. This work, whether done for tribal migrations or war parties, is usually done by a scout or scouts. When a man travels alone, of course, he must be his own scout. Similarly it is common for lone travelers or small parties to avoid open spaces without cover, where this is possible, and where it is not possible, to cross them expeditiously. An occasional ruse used in crossing an open terrain, incidentally, is to throw a kailiauk robe over oneself and bend down over the back of one's kaiila. From a distance then, particularly if one holds in one's kaiila, one and one's mount may be mistaken for a single beast, a lone kailiauk.